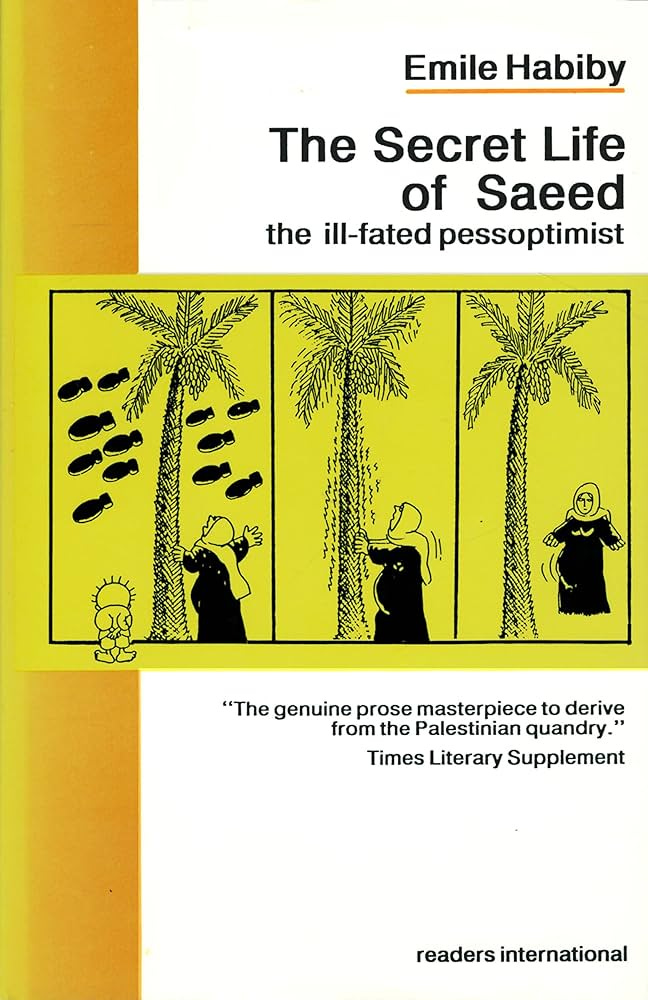

Emile Habibi's Secret Life of Saeed

Considered one of the finest works of Arab fiction after 1967...

Emile Shukri Habibi was born in Haifa in 1922 and received a Christian upbringing. Haifa was one of the more industrialized cities in Mandatory Palestine, with railroad workshops and an oil refinery: Habibi got a job at the latter. Like many educated Christian Arabs in urban areas, Habibi was attracted to Marxism and joined the Palestine Communist Party.

The experience of being an Arab Leftist inside Israel’s armistice borders is at the core of the laugh-out-loud tragicomic novel, his prose masterpiece of 1974: The Secret Life of Saeed.

But there’s a little more table-setting before we get there!

The PCP in Palestine went through tons of internal splitting. By the time of the Arab-Israeli War and Nakba of 1948, Habibi was part of a faction of the National Labor League (a splinter from the PCP) that supported the UN's partition proposal. They thought two independent ethno-states, in the context of driving out the British and keeping the other Arab states away, would be in service of anti-imperialism. (There were also crypto-Zionist corners of the Communist space under the Israeli state after its declaration, that believed Zionism had a progressive and anti-imperialist character.)

While the majority of Palestinians were permanently displaced by the Nakba, Habibi remained in Haifa, and became an Israeli citizen. From the 1950s on, Habibi devoted himself to electoral and parliamentary politics on behalf of MAKI, the Communist Party of Israel.

Habibi was a talented writer and speaker, and came to be a chief advocate for Arab interests within Israel's borders, as a member of the Knesset for MAKI's party bloc. He also served on delegations to various Israeli-Arab peace conferences, Soviet Communist Party congresses, and joint meetings with various Egyptian Communist outfits.

However, he left politics to devote himself to full time writing by the end of the 60s, though he had been publishing stories and articles for a couple decades. The time was used to compose Saeed, a Palestinian novel as respected as it is unique in the stream of resistance literature. Not epic and tragic poetry, but picaresque prose.

It’s an epistolary novel: Saeed has written a series of letters in which he claims to have been whisked away from Palestine by “creatures from outer space.” So he may as well divulge his life story — and immediately we get that Saeed’s destiny is entangled with the image of the ass.

During the fighting in 1948 they waylaid us and opened fire, shooting my father, may he rest in peace. I escaped because a stray donkey came into the line of fire and they shot it, so it died in place of me. My subsequent life in Israel, then, was really a gift from that unfortunate beast. What value then, honored sir, should we assign to this life of mine?

Of course, Saeed sounds a lot like Voltaire’s hero Candide. What exactly is the nature of so-called “pessoptimism”?

That’s the way our family is and why we bear the name Pessoptimist. For this word combines two qualities, pessimism and optimism, that have been blended perfectly in the character of all members of our family since our first divorced mother, the Cypriot.

...Take me, for example. I don’t differentiate between optimism and pessimism and am quite at a loss as to which of the two characterizes me. When I awake each morning I thank the Lord he did not take my soul during the night. If harm befalls me during the day, I thank Him that it was no worse. So which am I, a pessimist or an optimist?

Once orphaned and displaced from his homeland, now part of Israel's territory, Saeed elects to sneak back in. He succeeds, but he finds himself working for the Palestinian Labor Union, an appendage of the big Hebrew trade union federation called the Histadrut.

In short, Saeed becomes an informant for the Zionist state, spying on and ratting out Communists and others posing a political threat to the colonial project.

Habibi’s humor is dark and macabre in a very liberating way, very similar to the Onion’s coverage of the current conflagration in the Gaza Strip. This is how Saeed reflects on how quickly Arab Palestinian proprietors picked up Hebrew: “This is not merely a case of necessity being the mother of invention; it is also a matter of the financial interests of a country’s elite who cared so little who ruled them politically that they applied in practice the Arabic proverb: Anyone who marries my mother becomes my stepfather.”

The chapter headings are done in the 18th century style: one of them is called “How Saeed Finds Himself in the Midst of an Arabian-Shakespearean Poetry Circle.” That “poetry circle” ends up being a circle of Israeli soldiers, surrounding Saeed as they beat him up inside a prison.

During the 1967 War (also called the “Six-Day War”), Arabs in the West Bank, which was seized along with East Jerusalem by Israel from Jordan, are instructed over the radio to raise white flags on their houses. Saeed, eager to show his compliance and good will to the state of Israel, makes his own white flag — even though he lives in Haifa.

The officials construe the ass Saeed to be a combatant in “occupied territory.” In a Catch-22-style scene between Saeed and his Jewish handler Jacob, the latter says: “The big man has come to believe that the extravagance of your loyalty is only a way of concealing your disloyalty.”

What’s the story with Saeed? Why is he such a self-abasing, eager puppy dog for the Zionist colonial occupiers? — and yet his good-for-nothing antics are at least perceived to be subversive, not at all unlike Jaroslav’s Hašek’s wartime hero Svejk, another big influence on the Pessoptimist.

It seems to be part of the experience being an Arab stuck as a second-class citizen within the state of Israel. It was effectively like being cut off from the resistance organizations that developed outside, in neighboring Arab states — and with that the pan-Arabist trend headed by Nasser in Egypt (which was the context for MAKI’s split into the all-Jewish rump Party and the Arab-majority RAKAH, which Habibi joined).

That’s why the police officer in the car taking Saeed to yet another prison complains about a certain Israeli Communist in the Knesset as “that stooge of Nasser, King Husain, the Emir of Kuwait, and Shaikh Qabus!”

There’s a great deal in the novel about searching for hidden treasures — and said treasures being confiscated by the Zionist government. A wife and son join the guerilla movement and walk into the sea, leaving the man behind.

And then, in the final part of the book, we seem to enter a predominantly phantasmagoric space, in which Saeed finds himself high up on a “stake.” He clings to it for a long while, while figures from his life come and go. He is suspended between a choice of staying in this hostile society or joining the diaspora as a refugee. It also feels like a parody of a saint’s martyrdom, or like the ascetic trials of Paphnuce in Anatole France’s novel.

The fundamental weakness of Saeed reflects that of MAKI in Israeli society in this period. It’s as if Saeed can’t see the situation unless from the view of a spaceship. Or perhaps it will take as much to bring a resolution to this 75-year conflict.

And now, and anecdote from Habibi’s days as a Communist activist.

In 1958, the reactionary rag Jerusalem Post had run an exaggerated report that MAKI members had met at Habibi's house in Nazareth to discuss forming a separate Arab Communist Party, which resulted in a firestorm and a serious wedge driven between Jewish and Arab leftists in Israel. But what had actually happened?

According to Emile Habibi, the incident resulted from an informal meeting of Arab party members in his house at which political topics were discussed, including the fact that young Palestinians in Cairo were thinking of establishing an armed movement. There was some excessive drinking, and at one point Habibi and Hanna Naqqara picked up the telephone, which they assumed was tapped, and shouted curses against the Jewish state into the receiver. Habibi’s version of the incident reflects badly on the discipline and moral stature of the Arab party leaders and for that reason may be at least partly true.

From Joel Benin’s Was the Red Flag Flying There?

Stay tuned for more reflections of the Palestine-Israeli conflict in literature.