William Faulkner. Go Down, Moses. Vintage International, 1990 [1942]. 365 pp.

Faulkner was simply on another level. I have to re-learn this lesson each time I decide to pick up one of his books. He makes a well-wrought fictive world and can render it in a tough-guy detective voice that seamlessly pivots to a gorgeous King James Bible register. And Faulkner was not just great but prolific. Beyond the four masterpieces (and the late Snopes Trilogy ), there is still the major work of Go Down, Moses.

Like Sound and the Fury we’re dealing with a troubled Southern family, like Absalom Absalom! there is an evil family secret of incest-miscegenation entanglement. But Go Down, Moses is also a cycle of short stories that take us from before the Civil War to 1942. We are invited to fill out the McCaslin (and Beauchamp) genealogy, step by step, generation to generation.

That being said, it’s read as a contained novel by and large, and the “And Other Stories” in the first edition cover hasn’t carried over to reprintings. An early version of “The Bear” appeared in Saturday Evening Post, and it’s by far the Faulkner story I’ve found anthologized the most often — it’s a monster of a story so it always stood out. But here it’s plain that “The Bear” depends so much structurally on what comes before, including a climactic scene with some farm bookkeeping.

The opening story, “Was,” is the only antebellum-set piece, and its events are absolutely fundamental.

It’s a story related to young Isaac McCaslin by his cousin McCaslin “Cass” Edmonds. (Not confusing at all.) When Cass was younger he went out riding with Uncle Buck (Theophilus McCaslin, Isaak’s father) and Uncle Buddy (Amodeus McCaslin) to the neighboring Beauchamp plantation to track down Tomey’s Turl who has run away. Is Tomey’s Turl a horse? that’s how the narrator and characters talk about him, like some beast of burden. But no, Tomey’s Turl is a slave who keeps sneaking out to visit his girlfriend, a Beauchamp plantation slave named Tennie.

After some funny mishaps, neighbor Herb Beauchamp challenges Buck to a single hand of poker — Buck calls in Buddy, who wins and Beauchamp must sell Tennie to the McCaslin farm so that she can marry Tomey’s Turl.

Tomey’s Turl himself deals the hand. Hubert tilts the lamp-shade: “the light moving up Tomey’s Turl’s arms that were supposed to be black but were not quite white, up his Sunday shirt that was supposed to be white but wasn’t quite either, that he put on every time he ran away just as Uncle Buck put on the necktie each time he went to bring him back…”

The ramifications of this poker game continue for another century.

For one thing, by 1941 Tennie’s and Turl’s son Lucas is now a Black wage worker on the McCaslin farm, conning a salesman out of his metal detector to look for buried treasure, in the story “The Fire and the Hearth.”

Then a quick hard-boiled story, “Pantaloon in Black,” with a beautiful description of logging work:

Then the trucks were rolling. The air pulsed with the rapid beating of the exhaust and the whine and clang of the saw, the trucks rolling one by one up to the skidway, he mounting the trucks in turn, to stand balanced on the load he freed, knocking the chocks out and casting loose the shackle chains and with his cant-hook squaring the sticks of cypress and gum and oak one by one to the incline and holding them until the next two men of his gang were ready to receive and guide them, until the discharge of each truck became one long rumbling roar punctuated by grunting shouts and, as the morning grew and the sweat came, chanted phrases of song tossed back and forth. He did not sing with them.

The next group of three stories get to the core of the McCaslin clan narrative.

“The Old People” serves an ideal leadup to “The Bear,” and it’s also a fine hunting story in its own right. We’re introduced to “the boy,” young Ike McCaslin, and his mentor Sam Fathers as the boy gets his first serious kill, a buck. Sam Fathers, half-Black and half-Chickasaw, anoints the boy with the buck’s blood.

The boy did that — drew the head back and the throat taut and drew Sam Fathers’ knife across the throat and Sam stooped and dipped his hands in the hot smoking blood and wiped them back and forth across the boy’s face.

When Ike shares this with his cousin Cass Edmonds, the boy thinks at first that Cass doesn’t believe him. But — classic twist of the monster story — Cass believes him, because Sam Fathers did the same to him, took him to a clearing with a tree where a buck was waiting to be slain.

“And the earth dont want to just keep things, hoard them,” Cass says, “it wants to use them again. Look at the seed, the acorns, at what happens even to carrion when you try to bury it: it refuses too, seethes and struggles too until it reaches light and air again, hunting the sun still.”

The initiation rites continue in “The Bear,” where that titular forest warden, Old Ben, stands in for the awesome totality of the old woods:

It loomed and towered in his dreams before he even saw the unaxed woods where it left its crooked print, shaggy, tremendous, red-eyed, not malevolent but just big, too big for the dogs which tried to bay it, for the horses which tried to ride it down, for the men and the bullets they fired into it; too big for the very country which was its constricting scope. It was as if the boy had already divined what his senses and intellect had not encompassed yet: that doomed wilderness whose edges were being constantly and punily gnawed at by men with plows and axes who feared it because it was wilderness, men myriad and nameless even to one another in the land where the old bear had earned a name, and through which ran not even a mortal beast but an anachronism indominable and invincible out of an old dead time, a phantom, epitome and apotheosis of old wild life which the little puny humans swarmed and hacked at in a fury of abhorrence and fear like pygmies about the ankles of a drowsing elephant;…

Old Ben is near godlike, like something out of Princess Mononoke: he warns the little bears when the hunters are coming. It’s an entire project of the hunting party, specifically Boon Hogganbeck, to find the right hunting dog crazy enough to take the bear down. It’s a genuinely action-packed sequence when they finally do, and Old Ben takes a couple characters down with him.

And just like that, Isaac is a young man, poised to inherit the plantation. But Isaac the tempered woodsman doesn’t want this ownership, and prefers to hand the property over to his cousin McCaslin Edmonds.

“It was never mine to repudiate,” he says. “It was never Father’s and Uncle Billy’s to bequeath to me to repudiate because it was never Grandfather’s to bequeath them to bequeath me to repudiate because it was never old Ikkemotubbe’s to sell to Grandfather for bequeathment and repudiation.”

It’s not just his respect for nature: Isaac repudiates the whole situation of the South. The gothic secret is within the old plantation ledgers that Ike has studied, written in the hands of Uncles Buddy and Buck in different entries, and they practically exchange messages in some parts.

A sordid story of chattel/sexual slavery is slyly encoded in these entries:

Eunice Bought by Father in New Orleans 1807 $650. dolars. Marrid to Thucydus 1809 Drownd in Crik Cristmas Day 1832

June 21th 1833 Drownd herself

[…]

Tomasina called Tomy Daughter of Thucydus @ Eunice Born 1810 dide in Child bed June 1833 and Burd. Yr stars fell

[…]

Turl Son of Thucydus @ Eunice Tomy born Jun 1833 yr stars fell Fathers will

[…]

Tennie Beauchamp 21yrs Won by Amodeus McCaslin from Hubert Beauchamp Esqre Possible Strait against three Treys in sigt Not called 1859 Marrid to Tomys Turl 1859 [That Poker game in “Was”]

[…]

Lucas Quintus Carothers McCaslin Beauchamp. Last surviving son and child of Tomey’s Terrel and Tennie Beauchamp. March 17, 1874

In short, Lucas Quintus Carothers McCaslin, Ike’s grandfather, “got a child on” his slave Eunice, and then had a child with Eunice’s daughter Tomey, prompting Eunice to commit suicide shortly before Tomey gave birth to Tomey’s Turl.

Isaak has abandoned his father’s estate, but he does not quit the woods. For in “Delta Autumn,” the next story, a coda for “The Bear,” and a sublimely beautiful piece of prose, he’s an old man pushing eighty and still going on the annual hunt to the Bottom, now with the grandsons of the original party members of Major de Spain.

The landscape has drastically changed:

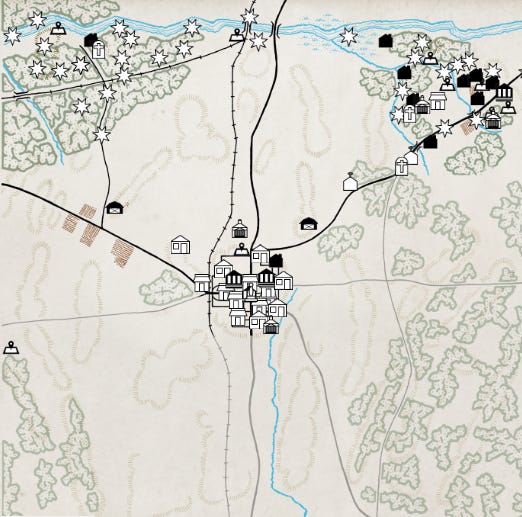

At first there had been only the old towns along the River and the old towns along the hills, from each of which the planters with their gangs of slaves and then of hired laborers had wrested from the impenetrable jungle of water-standing cane and cypress, gum and holly and oak and ash, cotton patches which as the years passed became fields and then plantations. The paths made by deer and bear became roads and then highways, with towns in turn springing up along them and along the rivers […]

Now a man drove two hundred miles from Jefferson before he found wilderness to hunt in. […] the land across which there came now no scream of panther but instead the long hooting of locomotives […]

The awesome wilderness has “withdrawn,” as a person may withdraw into the self with old age. There’s also a sense in Isaak’s mind that the destruction of nature by industry is God’s Judgment on the South for the horrible legacy of slavery and exploitation, “the old wrong and shame itself.”

He looks back on his first kill, when Sam Fathers anointed him: “I slew you; my bearing must not shame your quitting life. My conduct forever onward must become your death…”

The story climaxes with an encounter between Ike and the mistress of Cass’s grandson Roth. The woman is a distant cousin of Beauchamp’s. She is educated, and white-passing. Ike knows the truth: she’s a great granddaughter of Tomey’s Turl, and the baby is, once again, a product of incest and miscegenation.

We leave Ike in this disturbed state, thinking of “Chinese and African and Aryan and Jew, all breed and spawn together until no man has time to say which one is which nor cares.”

The final titular story goes outside the McCaslin clan, where the funeral procession of the youngest Beauchamp, grandson Samuel who killed a cop in Chicago, is witnessed by Gavin Stevens, a white attorney and amateur sleuth (he helps to clear Lucas Beauchamp’s name in Intruder in the Dust). When the hearse disappears over the horizon to go back to the McCaslin plantation, we stay with Stevens looking on.

Gavin Stevens is as good as a white Southerner in the mid-century can be within Faulkner’s universe, which isn’t so great indeed. I don’t simply mean the persistent racial insensitivity that’s appalling by our standards, but his refraining to question or denounce the gallant southern identity. He doesn’t have Old Ike’s existential pessimism, and he’s not a lost-cause type of ideologist either.

But he seems most aligned with the author’s own stated attitudes against Yankee intervention in regional matters. The most sympathetic way to put it is that he wanted the South to take responsibility for its own legacy of exploitation and racism, but in a way that still asserted political independence.

Still, back in the second story, Lucas couldn’t snitch on his opponent Wilkins for producing moonshine and be taken seriously by the authorities. But his grandson’s death and funeral will be reported in the paper just like anybody else’s. The poor souls of Yoknapatawpha may live in hope yet.