Joseph Conrad's Secret Agent

A most unwanted man...

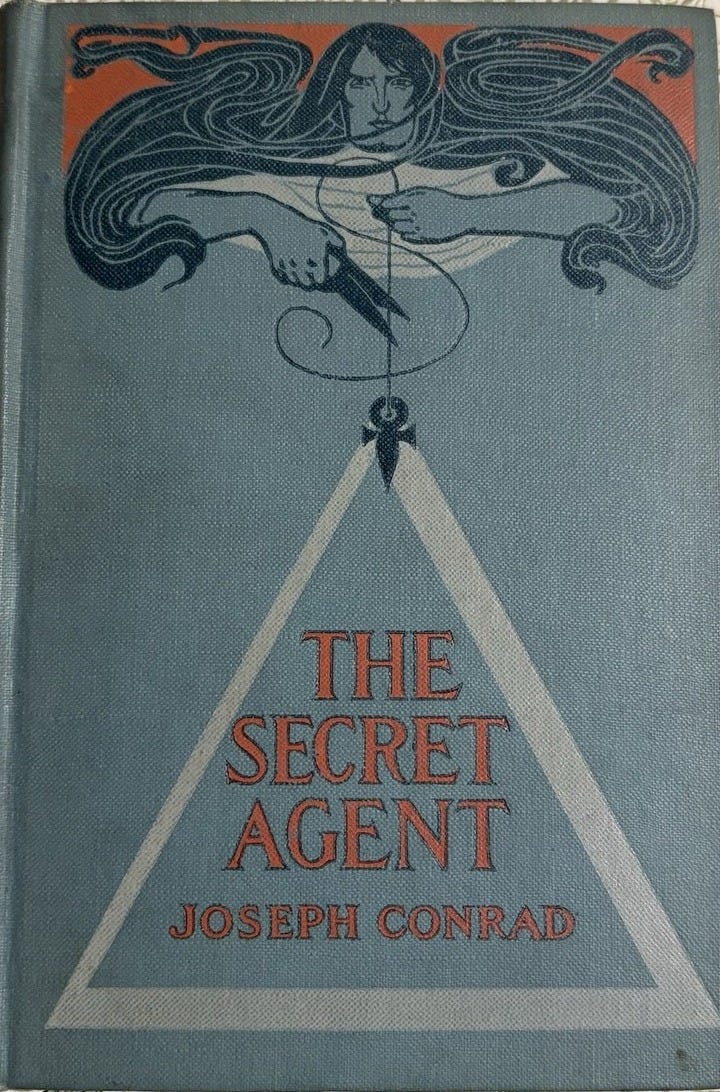

Joseph Conrad. The Secret Agent: A Simple Tale. Bernhard Tauchnitz, 1907. 312 pp.

Your host underwent a little bit of a “psychotic episode,” and read five volumes of the Kent collected edition of Joseph Conrad, which has been a reading project on here for the last couple years.

Still intriguing is the non-chronological order of titles. This one under review sticks out, after two tropical narratives from the Lingard trilogy — Almayer’s Folly and The Rescue — since it’s set entirely landbound and in gloomy London; maybe it’s serving as a palate cleanser.

Conrad wrote The Secret Agent after his masterpiece Nostromo, and maybe he wanted a break from that kind of sprawling historical caper with this “simple tale” of a thriller. If nothing else, one will know about The Secret Agent is that “it’s the one about the anarchist terrorists.” Conrad had dim views of the political philosophy that was all the rage in the late 19th century. From his preface, he talks about

the criminal futility of the whole thing, doctrine, action, mentality; and on the contemptible aspect of the half-crazy pose as of a brazen cheat exploiting the poignant miseries and passionate credulities of a mankind always so tragically eager for self-destruction. That was what made for me its philosophical pretenses so unpardonable.

You’ll get the feeling from the absurdist, black comic tone of this noir. But lest you take Conrad’s distaste for the subject as a refusal of imagination, he has us know that, like the great method actors of the 20th century, he can imagine himself into becoming even more of an anarchist than an actual anarchist.

I have no doubt, however, that there had been moments during the writing of the book when I was an extreme revolutionist, I won't say more convinced than they but certainly cherishing a more concentrated purpose than any of them had ever done in the whole course of his life.

That’s the spirit, Joe.

What’s clear right away is that Conrad is making an homage to his hero Charles Dickens, both in scene-setting and in the use of caricature. We’re introduced to Verloc, the titular secret agent, a phony anarchist and provocateur-asset for a foreign country, walking through the city streets, and the narration slips from depicting his movements to ironically depicting his character:

Before reaching Knightsbridge, Mr Verloc took a turn to the left out of the busy main thoroughfare, uproarious with the traffic of swaying omnibuses and trotting vans, in the almost silent, swift flow of hansoms. Under his hat, worn with a slight backward tilt, his hair had been carefully brushed into respectful sleekness; for his business was with an Embassy. And Mr Verloc, steady like a rock—a soft kind of rock—marched now along a street which could with every propriety be described as private. In its breadth, emptiness, and extent it had the majesty of inorganic nature, of matter that never dies. The only reminder of mortality was a doctor’s brougham arrested in august solitude close to the curbstone.

We never learn explicitly what nation Verloc’s handler works for, but his name is Vladimir, so, y’know… His lines are pablum as far as revolutionary rhetoric goes, but the motivations for the bombing attack he wants Verloc to set up seems to reflect the intellectual positivism of the era:

Art has never been their fetish. It’s like breaking a few back windows in a man’s house; whereas, if you want to make him really sit up, you must try at least to raise the roof. There would be some screaming of course, but from whom? Artists— art critics and such like — people of no account. Nobody minds what they say. But there is learning — science. Any imbecile that has got an income believes in that. He does not know why, but he believes it matters somehow. It is the sacrosanct fetish. All the damned professors are radicals at heart. Let them know that their great panjandrum has got to go too, to make room for the Future of the Proletariat.

Later on, when Vladimir learns in a conversation with the Assistant Commissioner that the English police are onto Verloc, he experiences the “change of his opinion” of Scotland Yard is experienced as something like an internal revolution:

But in his heart he was almost awed by the miraculous cleverness of the English police. The change of his opinion on the subject was so violent that it made him for a moment feel slightly sick. He threw away his cigar, and moved on.

The anarchist cell Verloc reports to is a chance for Conrad to get into Dickens style cartooning when it comes to physical appearance. Take Yundt “the terrorist”:

The terrorist, as he called himself, was old and bald, with a narrow, snow-white wisp of a goatee hanging limply from his chin. An extraordinary expression of underhand malevolence survived in his extinguished eyes. When he rose painfully the thrusting forward of a skinny groping hand deformed by gouty swellings suggested the effort of a moribund murderer summoning all his remaining strength for a last stab. He leaned on a thick stick, which trembled under his other hand.

Out of all of these weirdos, Michaelis “the apostle” has ideas that are most recognizably something close to historical materialism, though he’s also an intellectualist.

Michaelis by staring unwinkingly at the fire had regained that sentiment of isolation necessary for the continuity of his thought. His optimism had begun to flow from his lips. He saw Capitalism doomed in its cradle, born with the poison of the principle of competition in its system. The great capitalists devouring the little capitalists, concentrating the power and the tools of production in great masses, perfecting industrial processes, and in the madness of self-aggrandisement only preparing, organising, enriching, making ready the lawful inheritance of the suffering proletariat.

But the key link of this story is not the anarchists but Verloc’s home life, with his long-suffering wife Winnie and her mentally disabled brother, whom Verloc clearly regards as a burden.

For some time Mrs Verloc remained quiescent, with her work dropped in her lap, before she put it away under the counter and got up to light the gas. This done, she went into the parlour on her way to the kitchen. Mr Verloc would want his tea presently. Confident of the power of her charms, Winnie did not expect from her husband in the daily intercourse of their married life a ceremonious amenity of address and courtliness of manner; vain and antiquated forms at best, probably never very exactly observed, discarded nowadays even in the highest spheres, and always foreign to the standards of her class. She did not look for courtesies from him. But he was a good husband, and she had a loyal respect for his rights.

The plot jumps forward and back in time in a jarring way, around a singular bomb attack — the anarchists realize Verloc has done an adventurist job, with explosives provided by the obnoxious Professor. Meanwhile the brother-in-law Stephen has disappeared.

It is a long, drawn out dialogue scene in which Winnie wears Verloc down and learns the truth, which is so macabre yet pathetically funny, as is Verloc’s rationale and gaslighting of his wife over a grating number of pages. The tension finds its release in a fatal stabbing. But even after a matricide there’s more misfortune in store for poor Winnie.

Recalling these events lets me understand why there was such an outcry against the alleged misanthropy and meanspirited nature of this absurdist crime tale — it’s similar to the critical knocks against Fargo or Burn After Reading. Conrad’s reply to the charge in his author’s note is pretty funny:

I will submit that telling Winnie Verloc’s story to its anarchistic end of utter desolation, madness, and despair, and telling it as I have told it here, I have not intended to commit a gratuitous outrage on the feelings of mankind.

Beyond this near parodic thriller painted in the shades of Bleak House, there’s something to this narrative about perceiving other nations and international events. The Assistant Commissioner chides Vladimir from looking at Western Europe “from the other end,” and Conrad’s own considered if stubborn views of “national psychology” have been a pattern in our systematic readthrough of his work — and just wait till we get to Schomberg again in Victory…