Joseph Conrad. The Rescue — A Romance of the Shallows. J. M. Dent & Sons, 1920. 416 pp.

For this weekend edition of Silent Friends, he’s back!!

After 16 months, we’re resuming the journey through Joseph Conrad’s complete works, as compiled in the Kent Edition.

We had left off with his first novel Almayer’s Folly, and while today’s text comes from the end of Conrad’s life and career, The Rescue is in fact a sequel/prequel, presenting another adventure with Tom Lingard in the East Indies.

Conrad had started work on this project right after Almayer but he put it away, and wrote published the “third” entry of the Lingard trilogy (Outcast of the Islands) right after. Only in 1920 did he publish Rescue, to great popular and critical acclaim, and just four years before his death. It’s gratifying to know Conrad got some public recognition in his lifetime.

The Rescue had been laid aside in draft form because Conrad was distracted by producing some random minor works like Heart of Darkness and Lord Jim. In the Author’s Note, he talks about the particular difficulty of returning to this project decades later, making it sound like an epic voyage.

As I moved slowly towards the abandoned body of the tale it loomed up big amongst the glittering shallows of the coast, lonely but not forbidding. There was nothing about it of a grim derelict. It had an air of expectant life.

So the revival of this book was like a rescue in itself.

Conrad was firing on all cylinders with this long text rendered in a Jamesian “late realist” style, but full of vibrant characters and action. As the author wrote to Edward Garnett (and it’s been quoted on this Sub before), “No analysis. No damned mouthing. Pictures — pictures — pictures.”

And yet, for apparently being a simple adventure yarn, your host took down roughly triple the amount of notes as I normally do for these book reviews. So the richness of The Rescue was a pleasant surprise.

There was no wind, and a small brig that had lain all the afternoon a few miles to the northward and westward of Carimata had hardly altered its position half a mile during all these hours. The calm was absolute, a dead, flat calm, the stillness of a dead sea and of a dead atmosphere. As far as the eye could reach there was nothing but an impressive immobility. Nothing moved on earth, on the waters, and above them in the unbroken lustre of the sky. On the unruffled surface of the straits the brig floated tranquil and upright as if bolted solidly, keel to keel, with its own image reflected in the unframed and immense mirror of the sea. To the south and east the double islands watched silently the double ship that seemed fixed amongst them forever, a hopeless captive of the calm, a helpless prisoner of the shallow sea.

Thus Conrad takes us back to the hazy, dream-like seascape of the shallows, where, becalmed on his trusty two-mast brig Lightning, we’re reunited with the badass Captain Lingard (“He was about thirty-five, erect and supple”).

As for his swift brig:

She represented a run of luck on the Victorian goldfields; his sagacious moderation; long days of planning, of loving care in building; the great joy of his youth, the incomparable freedom of the seas; a perfect because a wandering home; his independence, his love — and his anxiety. He had often heard men say that Tom Lingard cared for nothing on earth but for his brig — and in his thoughts he would smilingly correct the statement by adding that he cared for nothing living but the brig.

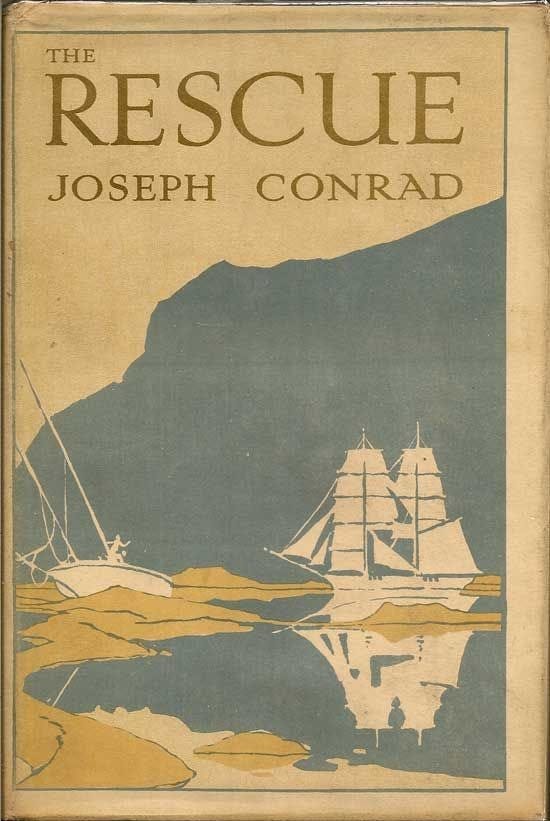

The becalming of the boat (and of the plot) is rectified by catching sight of a rowboat of folks whose pleasure yacht had gotten stuck in a muddy tidemark and are now searching for help. The yachters are marooned on an island where a lot of shady smuggling is done, and considering the sensitive nature of the situation, Lingard agrees to make a rescue. (So you can see that the illustration on the cover of the first edition above is quite accurate.)

Then we shift to members of the indigenous Wajo society in southern Indonesia, currently dominated by the colonial Dutch. Lingard is close friends with the leader Hassim (they had fought together in a Wajo civil war), and the narrator gives these interesting lines about the romance of war and trade, fused together in a “primitive” merchant capitalism.

They were natives of Wajo and it is a common saying amongst the Malay race that to be a successful traveller and trader a man must have some Wajo blood in his veins. And with those people trading, which means also travelling afar, is a romantic and an honourable occupation. The trader must possess an adventurous spirit and a keen understanding; he should have the fearlessness of youth and the sagacity of age; he should be diplomatic and courageous, so as to secure the favour of the great and inspire fear in evil-doers.

A whole bunch of elements from Lingard’s past, from Hassim and his fretful sister, to the old washed up captain Jorgeson, and an old vessel called Emma that’s functioning as a floating battery, are going to come together.

But in the meantime, Lingard makes it to the grounded yacht, but his man’s-man adventurer aura leads to a cold welcome. There is Edith Travers, who seems fascinated by Tom, but her husband is incensed: “He underrated my intelligence; and what a violent scoundrel! The existence of such a man in the time we live in is a scandal.”

Tom and Mr. T butt heads for a while, and Edith on the side has to laugh at the dick-measuring:

“No, but this is—such—such a fresh experience for me to hear—to see something—genuine and human. Ah! ah! one would think they had waited all their lives for this opportunity—ah! ah! ah! All their lives—for this! ah! ah! ah!”

But then we go further into Edith’s world, which has been genuinely rocked by the entrance of Tom:

Her thoughts, like a fascinated moth, went fluttering toward that light — that man — that girl, who had known war, danger, seen death near, had obtained evidently the devotion of that man. The occurrences of the afternoon had been strange in themselves, but what struck her artistic sense was the vigour of their presentation. They outlined themselves before her memory with the clear simplicity of some immortal legend. They were mysterious, but she felt certain they were absolutely true. They embodied artless and masterful feelings; such, no doubt, as had swayed mankind in the simplicity of its youth. She envied, for a moment, the lot of that humble and obscure sister. Nothing stood between that girl and the truth of her sensations. She could be sincerely courageous, and tender and passionate and — well — ferocious. Why not ferocious? She could know the truth of terror — and of affection, absolutely, without artificial trammels, without the pain of restraint.

Lingard is extremely awkward and impatient with the yacht folks, but he’s also frank and compelling in Edith’s eyes. When her husband Mr. T and their friend d’Alcacer get kidnapped by some natives on the island, Lingard moves Mrs. Travers to his brig and draws up a plan to extract the hostages, with Hassim’s help.

Then another Wajo warlord named Daman gets involved, and we read many passages like this one on the colonial encounter from his perspective.

Why, asked Daman, did these strange whites travel so far from their country? The great white man whom they all knew did not want them. No one wanted them. Evil would follow in their footsteps. They were such men as are sent by rulers to examine the aspects of far-off countries and talk of peace and make treaties. Such is the beginning of great sorrows.

The discourse continues between Daman and Hassim and his sister Immada (whom Edith thinks Tom likes, while Tom thinks Edith likes d’Alcacer).

Why, asked Daman, did these strange whites travel so far from their country? The great white man whom they all knew did not want them. No one wanted them. Evil would follow in their footsteps. They were such men as are sent by rulers to examine the aspects of far-off countries and talk of peace and make treaties. Such is the beginning of great sorrows. The Illanuns were far from their country, where no white man dared to come, and therefore they were free to seek their enemies upon the open waters. They had found these two who had come to see. He asked what they had come to see? Was there nothing to look at in their own country?

Thanks to Lingard’s charisma among Hassim’s Wajo faction, the temporary release of the hostages is secured. But this leads to a nasty conversation between husband and wife, with an embittered and fever-ridden Mr. T telling her:

“It's my belief, Edith, that if you had been a man you would have led a most irregular life. You would have been a frank adventurer. I mean morally. It has been a great grief to me. You have a scorn in you for the serious side of life, for the ideas and the ambitions of the social sphere to which you belong.”

He stopped because his wife had clasped again her hands behind her head and was no longer looking at him.

She can barely stay in the same room as this man, but she is resigned to stay with him for the rest of her days.

And when a wrinkle emerges in the rescue scheme, thanks to the ironic doings of Mr. Carter, a young member of the yacht crew, d’Alcacer has his own turn of racial bitterness:

“Pah! I shall be probably speared through the back in the beastliest possible fashion,” he thought with an inward shudder. It was certainly not a shudder of fear, for Mr. d'Alcacer attached no high value to life. It was a shudder of disgust because Mr. d'Alcacer was a civilized man and though he had no illusions about civilization he could not but admit the superiority of its methods. It offered to one a certain refinement of form, a comeliness of proceedings and definite safeguards against deadly surprises. “How idle all this is,” he thought, finally. His next thought was that women were very resourceful. It was true, he went on meditating with unwonted cynicism, that strictly speaking they had only one resource but, generally, it served — it served.

Among all the moving pieces, there is an interesting layer where we see these characters making various racially/chauvinistically motivated choices. Lingard’s crazy first mate Shaw is way more sympathetic to these leisure class snobs on the yacht, while Lingard reflects on how he feels much more at home with the Malays after all these years uprooted from England. There’s a lot of misunderstandings and missed connections, and the whole thing ends with a note of deep loneliness. Great freedom of movement here in the Shallows, yes, but profoundly lonely.

Far away in its depth a couple of feeble lights twinkled; it was impossible to say whether on the shore or on the edge of the more distant forest. Overhead the stars were beginning to come out, but faint yet, as if too remote to be reflected in the lagoon. Only to the west a setting planet shone through the red fog of the sunset glow.