László Krasznahorkai. The Melancholy of Resistance. Translated from the Hungarian by George Szirtes. New Directions: 2000 [1989]. 314 pp.

I don’t like to play up “difficulty” in novels, but I’ve got to admit this book was brutal to read. And it’s probably Krasznahorkai’s masterpiece to this day.

The Melancholy of Resistance, the Hungarian maestro’s second novel, was genuinely challenging in its sheer molecular density of text, like Faulkner’s Absalom Absalom!. It has a way of hypnotizing you…it’s quite unsettling, a process of conceptual suffocation. And yet it’s not Finnegans Wake or like Henry James either. In the fictive world of this dark, apocalyptic story, it’s very much ‘what you see is what you get.’

It’s a novel of compulsive, monomaniacal focus. It confronts the reader with the kind of cognition that could only be born of a desperate situation with nothing to cling to but ideology. Again, it could be Don László’s masterpiece, produced before his pivot into more transcendental subjects — it simply has the most sauce out of everything I’ve read of his work so far.

In this project of blogging L. K.’s main sequence of novels — Satantango, Melancholy of Resistance, War & War, Baron Wenkheim’s Homecoming — I want to seriously take up the author’s oft-quoted statement from his interview for Paris Review in 2018: that these novels were composed as iterations of “the same book,” and now taken together they are the “one book.”

Once again we look in on a mittel-European community, and though it’s a little town instead of a farm, it feels no less parochial than the setting of Satantango. Once again, a story spanning only a handful of hours takes on the feeling of a prose epic in miniature. Once again an inscrutable outsider arrives, towing along an exhibit of a giant stuffed whale. (When Sebald said this novel creates “a world into which the Leviathan has returned,” I assume that’s what he had in mind.)

However, Melancholy presents a huge increase in formal rigor relative to Krasznahorkai’s debut Satantango. These giant block paragraphs, running up to 60 pages, represent massive unhewn units of narrative time. And the meaning of time in this novel is taken up with sauntering from point A to point B, or lying around thinking and reading. Time is the medium of thinking, rather than doing. The action is stripped down to short trips, gazes and gestures — even as absurd and senseless violence is taking place all around.

There is some kind of riot or pogrom in the town square; the army comes to bring order; the only decent humans of the story come to bad ends while the dim and cynical exploit the crisis and come out high on the hog. (Not at all like in the real world! — Ed.) It’s a text about political chaos and mass violence yet its allegorical air doesn’t refer to anything explicit, though the imminent collapse of Soviet social imperialism must be a consideration. It’s hard to tell what year it is in these narratives, which is a big strength.

…no one could believe that thirty years after the Flowering of the Nation, with its high-sounding plans, there should still remain so large a rabble of frightening, villainous-looking, good-for-nothing, possibly threatening characters thirsting after the crudest and most vulgar of miracles.

Your host isn’t even 100% certain that “Flowering of the Nation” refers to the rapid industrialization and collectivization in Hungary in the 50s, or the uprising in 1955, or if it points to anything historical at all.

What I am certain of is that the friendship between the elderly Mr. Eszther and the younger Janos Valuska at the core of this novel. Both are styled as savants, living in their own worlds, though these are intellectual rich realms indeed. Valuska has his head in the heavens, contemplating stars and planets and plumbing the cosmos for revelation.

While walking through the town, which is strangely filling up with people gathering at the square where the circus and whale are installed, Valuska has these zen-like thoughts amidst the crush of town dwellers:

there was something about drifting in this solemn flood of humanity in a state of cosmic awareness that made it seem the most natural of activities, and, hardly noticing the surprising multitude, he absorbed himself ever more deeply in what, for him, were moments of exaltation so intense that by the time he finally reached the market end of the boulevard again (his bag filled with some fifty copies of an old newspaper since, as he discovered at the depot, copies of the new ones had once again gone astray), he wanted to cry aloud that people should forget about the whale and gaze, each and every one of them, at the sky…

A town “looking for miracles,” drawn as if magnetized to the taxidermized whale (a hollowed-out state power? or a sign that Melvillian romanticism is dead?), and there’s only old news even though Valuska needs to cry out….

Eszther is at home in the infinite rationalisms of technical philosophy. They have a great rapport, Eszther and Valuska, but “the subject of the heavens…lay wholly in Valuska’s territory.” He thinks Valuska was inspired by “an image, something remembered from childhood perhaps, only an image, of some once-glimpsed universal order…”

He is a musicologist devoted to the “Werckmeister” harmonic scale system.

Ever since he was young he had lived with the unshakeable conviction that music, which for him consisted of the omnipotent magic of harmony and echo, provided humanity’s only sure stay against the filth and squalor of the surrounding world, music being as close an approximation to perfection as could be imagined,…

These lines stuck out because they’re reminiscent of a famous quote taken from Schopenhauer on music:

The inexpressible depth of all music, by virtue of which it floats past us as a paradise quite familiar and yet eternally remote, and is so easy to understand and yet so inexplicable, is due to the fact that it reproduces all the emotions of our innermost being, but entirely without reality and remote from its pain.

And so, at the philosophical level, it’s hard not to read these thoughts as a sounding a conservative note, rooted in old European agrarianism, I mean “rooted in the soil” kind of thinking, which has a strong influence on the kind of agnosticism this text is expressing.

A set piece in the book’s center concerns Mr. Eszter hammering a nail in a board in the process of barricading his home, in anticipation of the imminent mob. It is an unbroken paragraph running 30-40 pages. How is it possible to span this much text around an action so rudimentary? Let’s just see.

“You have to get the details right. Focus on the details,” he says to himself. He’s hit himself twenty times, he has “shamefully neglected the art of putting hammer to nail…”. But always the deep thinker, Mr. Eszter starts formulating in real time a philosophy of hammering nails: “The arc to be controlled is the one that determines the relationship between the head of the instrument and the head of the nail…”.

But through more analysis he realizes that what matters “is where I want the contact to take place,” and in more language revises his system thus far. “To judge by appearances, he summarized, the clear lesson was that the serious issue underlying this apparently insignificant task had been resolved by a persistent assault embodying a flexible attitude to permutations, the passage from ‘missing the point’ to ‘hitting the nail on the head’ so to speak, owing nothing, absolutely nothing, to concentrated logic and everything to improvisation….”

Is this whole thing a literalized, and therefore ironized, presentation of the two idioms of all idioms? It is, and it’s a send-up of academic prose. It’s reminiscent of Molloy and his “stones” that he keeps and transfers throughout his pockets while sucking them, “turn and turn about.” If Beckett’s character presents a spoof of “French” philosophy, math and pattern-driven as it has been since Descartes, then Melancholy satires the “Germanic” way of thought, writing brick-walled paragraphs that represent deranged systems, generated wholesale from a piece of woodwork, literally Kant’s writing desk in gloomy present-day Kaliningrad.

To get to the point (haw): this narrative can spend hours of reading time covering a handful of gestures and movements (from room to room in Ezsther’s home), because this novel emphatically demonstrates something all novels have, namely the capacity to explore inner space while retaining a sense of “real time.”

Your host has fallen in the habit of considering films and modern novels as not only related but like formal inversions of each other. Movies present outer space, even when the story is set in inner space, like The Wizard of Oz. Conversely, novels present inner space, even when the story is set in outer space, like Sebald’s mock-travelogues. “Outer space” here doesn’t necessarily mean spaceships and black holes but it definitely means externality: movie cameras still capture a mise en scene, while the novel’s text unfolds a purely conceptual structure for the reader to interpret.

Anyway, this sequence climaxes when Ezther’s philosophical digging leads to a core self-realization of his own drive to cognize everything as just being one big coping mechanism.

He adjusted his deep-claret-colored smoking jacket, linked the fingers of his hands together behind his neck, and, as he noticed the feeble ticking of his watch, suddenly realized that he had been escaping all his life, that life had been a constant escape, escape from meaninglessness into music, from music to guilt, from guilt and self-punishment into pure ratiocination, and finally escape from that too, that it was retreat after retreat, as if his guardian angel had, in his own peculiar fashion, been steering him to the antithesis of retreat, to an almost simple-minded acceptance of things as they were, at which point he understood that there was nothing to be understood, that if there was reason in the world it far transcended his own, and that therefore it was enough to notice and observe that which he actually possessed.

Eszther and Valuska seem to have an arc where they mutually disenchant each other, but at the same time Valuska looks up to Eszther as a teacher, and Eszther fondly regards Valuska as something like a symbol for his own hope. The sadness of this novel as I read it is that the world has no place for either of these guys. Valuska in particular, in the eyes of the victors of this crisis, simply represents “all the self-deluded, mystificatory, paralysed members of society” who “should simply be ‘swept away.’”

Even though it was the rational, administrative attitude that in part must have led up to this explosion of disorder and nihilism — who is truly mystified here?

The simple and kind Valuska ends up demonized by the town’s upper crust, when he had just been swept up in the malicious crowd. A key moment, however, occurs when in the morning after he picks up a notebook, one that had been carried by one of the marauders.

Was there a “set-up” for this notebook anywhere in the scenes of the mysterious circus folk? Had I missed it amongst the drift of the prose? I worried. But no, it simply appears. And this is another element of the novel’s challenge, since it is a highly “paratactic” narrative. Despite the clear causal process in the story’s backdrop, the plot is one scene, one character, one set of elements after another. The effect feels not only dense but flat.

At this point, Valuska picks up the notebook and starts to read, and something chilling unfolds.

….and then it made no different whether we bore left or right, we simply flooded every street and square, for one thing and one thing alone drove us and confronted us at every turn, a hollow sense of fear combined with resignation that left us with some hope of mercy; nor where there any orders or words of command, no attempt at calculation, no taking of risks and no danger, since there was nothing left to lose, everything having become intolerable, unbearable, beyond the pale;…

First of all, the first-person prose of this notebook is the same as the third person narrator’s, in terms of style, tone, register, syntax. It’s like opening a door to another world only for the new one to be just a monochromatic copy of the first one. It’s a textual mise en abyme.

And it may offer the perspective of the “mob,” but it has no real explanation for what’s going on. Is this fascism? “totalitarianism?” the intrinsic evil of the unwashed masses or what have you?

It’s a demonic/parodic vision of the masses in motion beyond any political goal: they’ve “nothing left to lose,” but crucially absent is the political “vision,” the world to win. The Melancholy of the novel’s title finds its sharpest expression here: the source of this violence is some vague intolerance for everything that directly exists, as well as a powerlessness inducing a collective blind rage.

And yet this moment of vertigo is also the clearest moment of “didacticism,” if you can call it that, for this is when the novel “teaches” you how to read it by focusing on Valuska’s immersion into this text. He reads “like a colt accommodating itself to the pace of his mother, he should tie himself as closely as possible to the headlong rush of the dark, galloping narrative…”

And when he gets to the end of the fragment he starts again from the beginning, “in the belief that what didn’t go down properly the first time might be fully absorbed the second time around.”

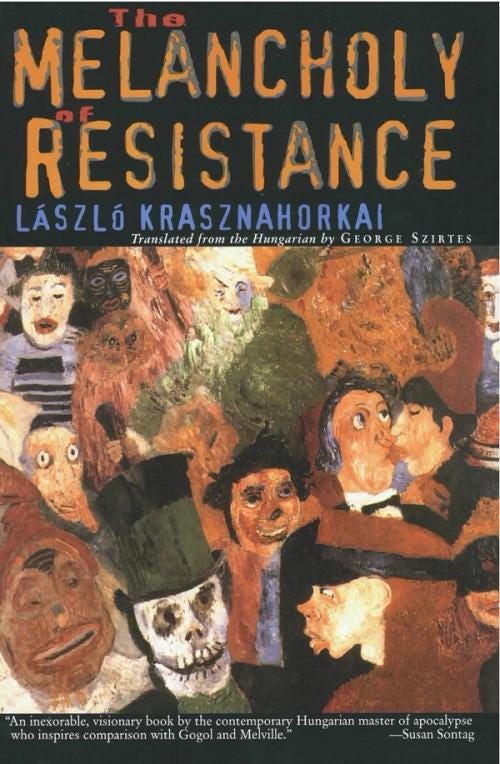

There’s a lot more to discuss in this rich novel. I didn’t even touch on the prologue and the epilogue that follow two very different female characters. Nor did I dwell on the final couple of pages that crank up the macabre and necrotic tone up to 11. This letter’s long enough, so to stay on the topic of the masses, we close by talking about the cover of the English version.

New Directions did a great job packaging Sirtzes’s translation, and likely determining L. K.’s first impression on that sphere, by choosing for the cover a detail from James Ensor’s massive and insane post-impressionist canvas. The detail comes from the bottom left corner, probably since the grotesque foreground figures have more detailed rendering — and it’s apparently also the spot of the painting that got damaged during World War Two, somewhere around the death’s head guy, appropriately enough.

The actual Christ of “Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889” (pictured above in this letter’s frontispiece) is further in the background. Riding on a donkey and surrounded by literal clowns, his own blushing complexion seems to resemble overdrawn clown makeup. His halo, golden like the iconography of devout Russian painters, is so flattened that it may as well be a sun hat pinched from a southern belle’s wardrobe. This is, at best, a dragged-up burlesque of the masses making history.

He’s handsome though, I’ll give him that (apparently a portrait of the artist).