There’s been a lot of interesting translated literature coming out of the larger indie and university presses for the last 15 months or so. That’s been the background to the recent and forthcoming letters, as well as a my review pieces this year.

But now it’s time to give a small notice to a wafer-thin book, a first-ever translation of an early work by Osamu Dazai.

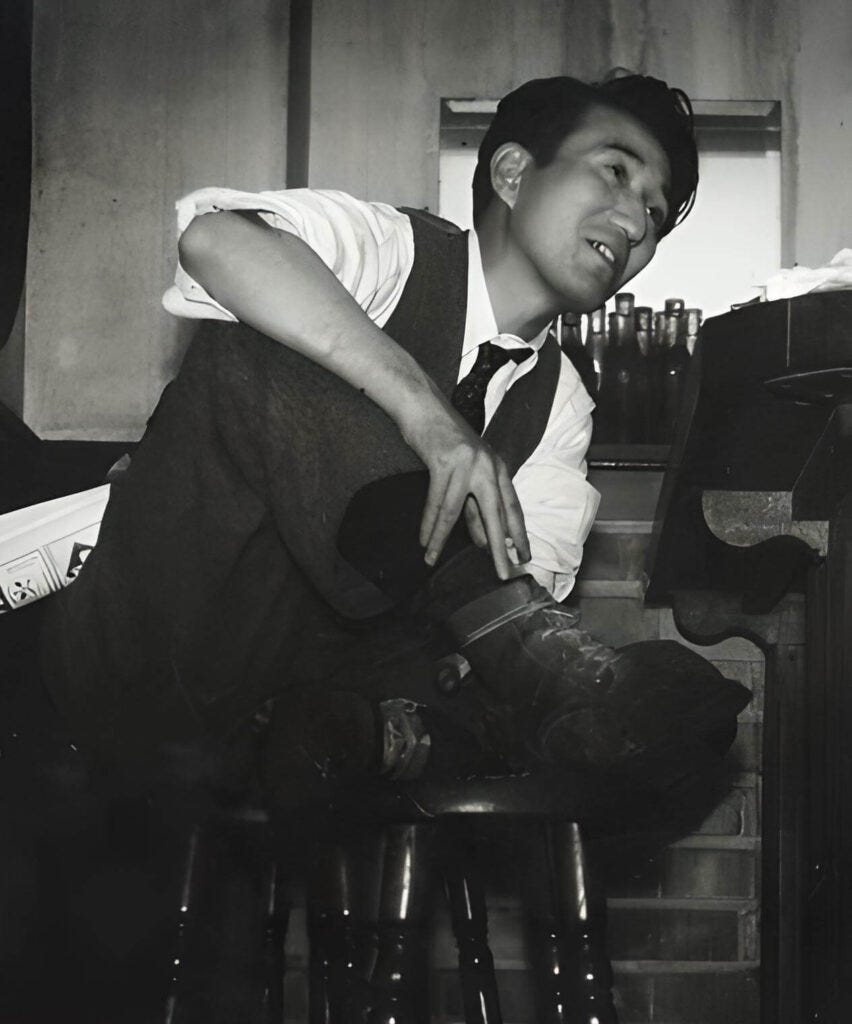

Osamu Dazai was the pen name of Shuji Tsushima, who became a leading light of Japanese post war fiction with his stories of doom, gloom, confusion, and black humor. He most often employed the shishōsetsu narrative form, inserting his authorial persona into his stories. Central to his body of work are unsuccessful suicide attempts. In 1948, he finally succeeded, in the Tamagawa Aqueduct in Tokyo.

The Flowers of Buffoonery has been translated by Sam Bett for the very first time, when his postwar classics like The Setting Sun have been here for quite a while, translated by the legendary Donald Keene.

The novella is basically about Yozo Oba, the narrator of Dazai’s most well-known work No Longer Human, waking up in a sanatorium after a botched double-suicide attempt with a woman who didn’t survive. This text, however, foregrounds the third-person narrator quite aggressively.

“To begin, who is this Yozo Oba character? I wrote him into being, drunk on a substance far more potent than alcohol. There could be no better name for my protagonist. ‘Oba’ flawlessly encapsulates his vigorous spirit, while ‘Yozo,’ I must say, has pizazz.”

“I might have skirted the whole issue by writing in the first person, but this past spring I wrote a novel with a first-person narrator, so I’m hesitant to do another one so soon.”

This novel is about Yozo “Yo-yo” Oba passing the time in the Blue Pines sanatorium with his fellow rich kid bohemian artist friends. While Yozo paints and subscribes to leftwing ideas about art, Higa is a sculptor and a Romanticist. The latter pouts “so much art world gibberish that anyone who heard him talk was embarrassed on his behalf.”

Meanwhile, Yozo argues that “A painting is just a glorified poster. […] Art is a proverbial turd, the byproduct of the socioeconomic complex. Social capital made manifest. Even the greatest masterpiece is no more than a commodity, just like a pair of socks.”

A chapter begins with some brief lines describing the calm sea and clear skies of the morning, only to break in with: “Never mind. I hate describing scenery.”

The buddies crack jokes and vibe out in the sanatorium. Yozo’s nurse Mano tells a ghost story involving a crab. Three or four days go by in the same leisurely fashion in this sub-100-page book, in Dazai’s clear style.

And that’s pretty much it. It never keeps up the tone of that initial art school debate above. The narrative is deliberately light and hollow. A certain line gets repeated: “Beautiful feelings make bad literature.” Sometimes the narrator takes it up proudly, other times calls it bullshit. And yet this was a kind of inspiring read.

The standard wisdom is that Dazai’s fourth wall-breaking addresses were inspired by André Gide. But one book Flowers repeatedly brought to mind was Mann’s Magic Mountain, not just because of the same setting of an elevated sanatorium, but the project of a perverted coming-of-age narrative. But Flowers of Buffoonery is not long but short, not exploring different ideologies but deflating them, not presenting possible ways of living outside the clinic, but suppressing the facts of life with comedy.

Now we have a kind of external key piece to No Longer Human in English, that also presents a more experimental aspect of Dazai. In fact, the title of the latter book has its origins in this book, in a phrase closer to the literal meaning of the Japanese, which is “no longer qualified to be human.”