Re-reading McCarthy's Blood Meridian

The riders rode on, and the movers all moved on again...

This letter is a chance to reflect quickly on my own relationship to McCarthy’s work. Especially considering he had just recently published new books for the first time since I was in middle school, and then died.

When I’d first heard about McCarthy, it was The Road that was causing such a firestorm. I was actually pretty late in coming to ‘serious literature’; this was my introduction, alongside Yann Martel’s Life of Pi and Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451.

But it was McCarthy’s work that opened up the limitless potential for evil in fiction.

While the “Border Trilogy,” starting with All the Pretty Horses in 1992, prompted the mainstream to give McCarthy more attention, his work in the 70s and 80s held such grotesque and violent visions, especially Child of God (1973).

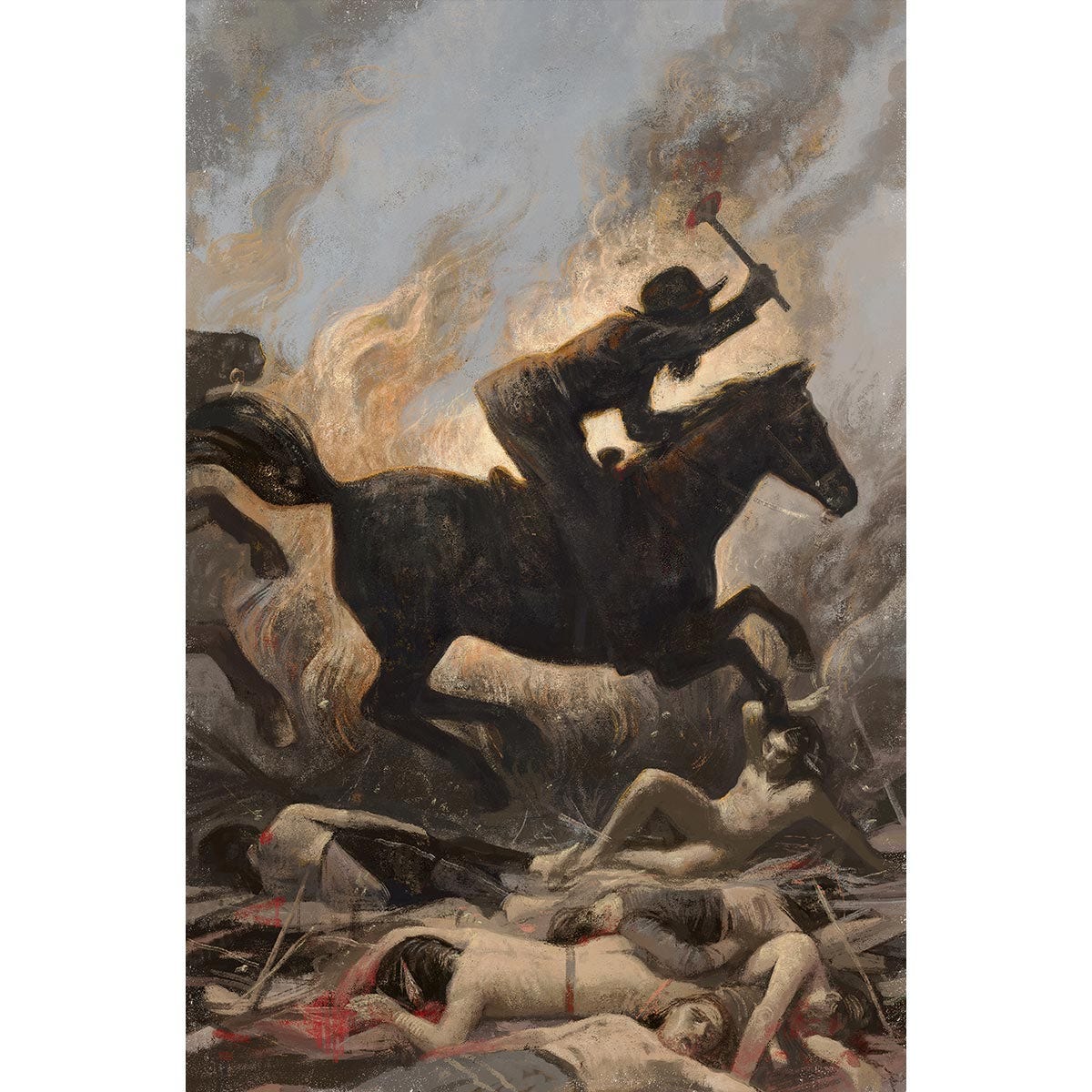

His aestheticized violence came to full flower in Blood Meridian. Unlike his prior Tennessee novels, this is an historical epic western. Indeed, it’s the Western to End all Westerns. The genre is known for its ethical simplicity, but the raids and pogroms against the indigenous as depicted in this work is more like an ethical annihilation.

Here is a swatch of the novel’s poetic prose, blending travelogue with war reportage and elevated King James Bible rhetoric into a fascinating mock-historical discourse:

And now the horses of the dead came pounding out of the smoke and dust and circled with flapping leather and wild manes and eyes whited with fear like the eyes of the blind and some were feathered with arrows and some lanced through and stumbling and vomiting blood as they wheeled across the killing ground and clattered from sight again. Dust stanched the wet and naked heads of the scalped who with the fringe of hair below their wounds and tonsured to the bone now lay like maimed and naked monks in the bloodslaked dust and everywhere the dying groaned and gibbered and the horses lay screaming.

It’s not only intense, but it’s decisively unreflective writing. We rarely get a glimpse into the inner meaning of these characters. It is very much like the literary experience Joseph Conrad described for his novel The Rescue, in a letter to Edward Garnett, as “a kind of glorified book for boys — you know. No analysis. No damned mouthing. Pictures — pictures — pictures.”

If certain readers are looking for a justification for the willful exteriority of this novel's style of narrating, the closest they may get is early on in the first chapter's first section, when the kid is running away from an obscure childhood to New Orleans. A passage of elevated language holds the kid in the midst of the transfer:

His origins are become remote as is his destiny and not again in the all the world's turning will there be terrains so wild and barbarous to try whether the stuff of creation may be shaped to man's will or whether his own heart is not another kind of clay.

I wanted to give this quote because the “wild and barbarous” conditions seem to necessitate this wildly distanced writing, to present this historical environment in which conduct of men is equally barbarous and inscrutable. But what about the two propositions at the end, whether humans shape nature or if humankind itself is to be shaped — this language evokes the labor process historically, the human vs. nature conflict, the “shaping to man's will” of nature to various degrees.

History is in fact a story of the domination of nature by humans, and the domination of nations and economic classes of humans over others.

Much has been written about the numinous, mystical, and theological radiations of this text, which this letter won't have the space to parse through. The economic basis for the novel's content, however, is also clearly present. Both the pre-Civil War US government and the federal republic of Mexico both hire Glanton's gang of scalpers: the earliest massacre sequences are in practice state-prompted pogroms against the indigenous, to ensure the stability of capitalist activity within the towns.

The captain leaned back and folded his arms. What we are dealing with, he said, is a race of degenerates. A mongrel race, little better than niggers. And maybe no better. There is no government in Mexico. Hell, there's no God in Mexico. Never will be. We are dealing with a people manifestly incapable of governing themselves. And do you know what happens with people who cannot govern themselves? That's right. Others come in to govern for them.

The coarser, material interests make themselves known, for which the racist colonial arrogance displayed above is the cloak:

I dont think there's any question that ultimately Sonora will become a United States territory. Guaymas a US port. Americans will be able to get to California without having to pass through our benighted sister republic and our citizens will be protected at least from the notorious packs of cutthroats presently infesting the routes which they are obliged to travel.

Judge Holden, the real leader of this death-dealing outfit, comes across as some larger-than-life, monumentally satanic figure. He'll callously murder unarmed people with a Henry Fonda-like glint in his eyes and apple dimples from his chipper smile. He's a pederast. He scalps a child. He's also conversant in dead languages and legal affairs. When he’s not ridin’ and shootin’, he's examining archeological specimens and taking scientific notes in his ledger.

Late in the novel, the scalpers are camping in a dry riverbed after leaving Tucson. Here the Judge makes his famous soliloquy about War:

War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That's the way it was and will be. That way and not some other way.

But when another scalper, named Brown, asks “What about all them notebooks and bones and stuff?” the Judge answers, “All other trades are contained in that of war.”

Once again, the utterance has multiple levels of meaning. McCarthy has a following of cult adulators, and it seems most of them take this meaning into a “universal,” Nietzschean world of endless war and will to power.

On this read-through, however, it seemed to point to the specific historical conditions of these events. Despite all the ponderous Gnostic musings from the judge, the narrator doesn’t lose sight of how the scalpers are supported by the government policies of an expansionist bourgeoisie — the same as that in Europe after the French Revolution. The armed expeditions not only cleared territory, but also collected a large influx of scientific knowledge. In a real sense, the trade of war did centralize the other trades, similar to Napoleons invasion of Egypt at the end of the 18th century.

At the same time, the violence of the scalpers only continues to exceed all limits. They senselessly attack a caravan of mules transporting silver:

The riders pushed between them and the rock and methodically rode them from the escarpment, the animals dropping silently as martyrs, turning sedately in the empty air and exploding on the rocks below in startling bursts of blood and silver as the flasks broke open and the mercury loomed wobbling in the air in great sheets and lobes and small trembling satellites and all its forms grouping below and racing in the stone arroyos like the imbreachment of some ultimate alchemic work decocted from out the secret dark of the earth’s heart, the fleeing stag of ancients fugitive on the mountainside and bright and quick in the dry path of the storm channels and shaping out the sockets in the rock and hurrying from ledge to ledge down the slope shimmering and deft as eels.

For the critic Dan Sinykin (whose 2020 book actually prompted this re-reading), this scene expresses a transition from the “primitive accumulation” process to “an irrational, apocalyptic force that performs a reductio ad absurdum on the capitalism — specifically US imperial capitalism — it was supposed to implement.”

This war of aggression started as a way to concentrate private property, but its agents soon take their aggression onto private property itself, perhaps most notably in the scene where Brown tries to get his shotgun sawed off.

Finally, a word on the title, since, Blood Meridian is of course an abbreviation. The evening redness in the west has no punctuation after the conjunction or, suggesting that it’s not really a subtitle in the normal sense.

The title drop comes when Glanton’s gang are camping within the ruins of the Anasazi people. The judge says:

The way of the world is to bloom and to flower and die but in the affairs of men there is no waning and the noon of his expression signals the onset of night. His spirit is exhausted at the peak of his achievement. His meridian is at once his darkening and the evening of his day.

These lines almost take us out of historical time, let alone the circadian rhythm of the planet. From the noontime of perfect violence, instantly to crimson evening with a bloody westering sun. A symbolist landscape painting, a pastiche of 19th century natural philosophy, all serving as a pedestal for the novel’s true ending: an italicized vignette of a West thoroughly domesticated.

McCarthy was surely one of our greats and there shall be more letters on this Silent BFF in the future.

This letter’s illustration was by Gérard DuBois, from the Folio Society edition.