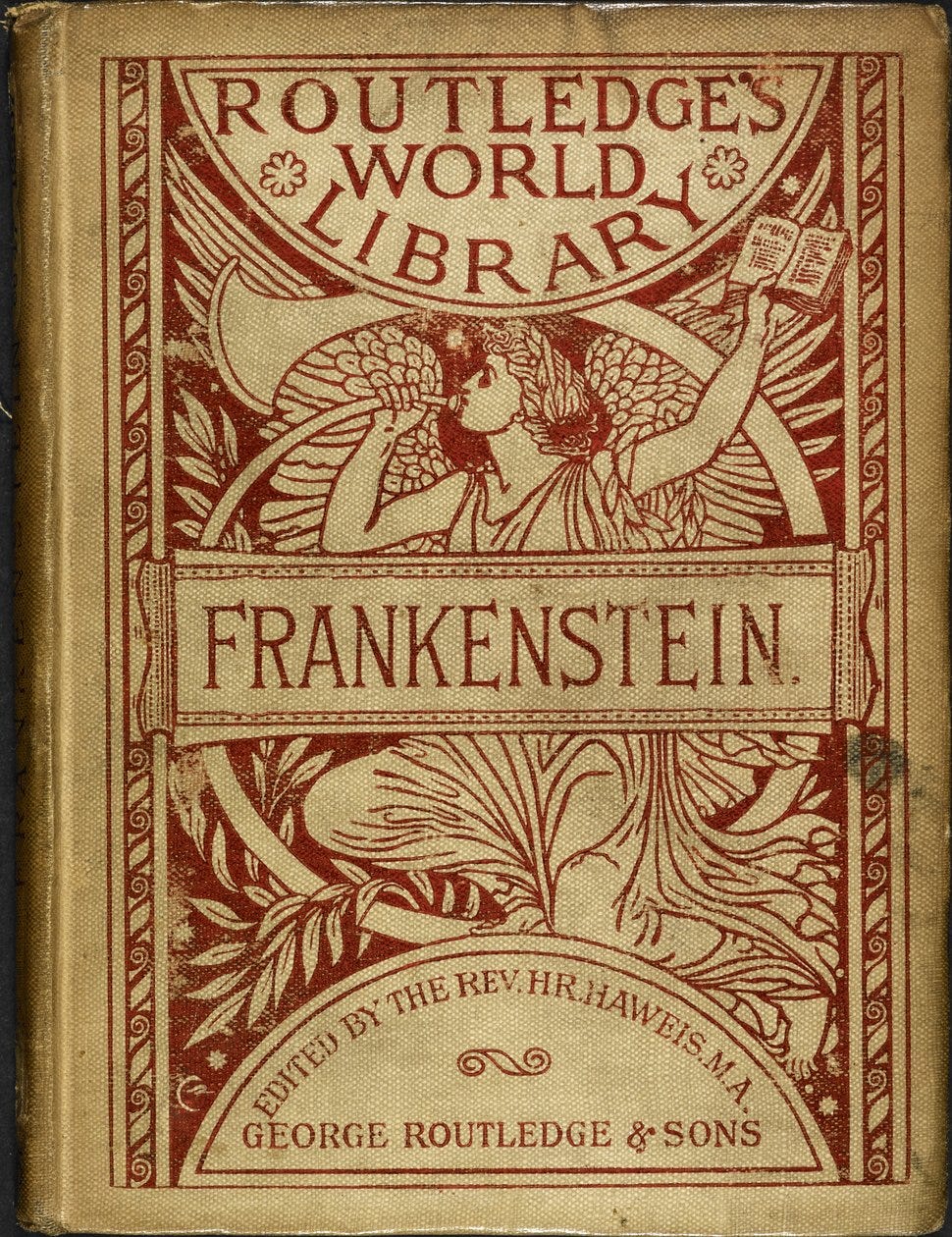

Mary Shelley. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. George Routledge and Sons, 1888 [1818]. 317 pp.

Ever since our 100th post special on vampires and Romanticism, Mrs. Shelley’s Frankenstein has been looming on the mind. It’s a gothic novel that I actually hadn’t completely read (British nineteenth century fiction is a huge blind spot for your host), but from its opening pages you can tell it’s very well-written. I ended up shredding this text with relish. Shelley wrote the hell out of this narrative, and when she was practically still a teenager!

A new movie version with Oscar Isaac has been announced, directed by del Toro, and the fans are encouraged by images of the framing scene in the arctic sea — this adaptation may be faithful to the original structure of the book. For Frankenstein’s monster in cinema has focused much more on the brass tacks of creating the Monster and his painful encounters with peasant society than Shelley’s allegories of instrumental rationality unchecked by Romanticist ethics leading to mayhem and murder.

It was appropriate to cover this text during Pride month, for the homosexual overtones are first sounded with the ship captain Robert Walton in the frame text. Witness the explicit yearning he shares with his sister Margaret in his correspondence:

But I have one want which I have never yet been able to satisfy, and the absence of the object of which I now feel as a most severe evil, I have no friend, Margaret: when I am glowing with the enthusiasm of success, there will be none to participate my joy; if I am assailed by disappointment, no one will endeavour to sustain me in dejection. I shall commit my thoughts to paper, it is true; but that is a poor medium for the communication of feeling. I desire the company of a man who could sympathise with me, whose eyes would reply to mine [!]. You may deem me romantic, my dear sister, but I bitterly feel the want of a friend. I have no one near me, gentle yet courageous, possessed of a cultivated as well as of a capacious mind, whose tastes are like my own, to approve or amend my plans. How would such a friend repair the faults of your poor brother! … I greatly need a friend who would have sense enough not to despise me as romantic, and affection enough for me to endeavour to regulate my mind.

[…]

Well, these are useless complaints; I shall certainly find no friend on the wide ocean, nor even here in Archangel, among merchants and seamen.

An aristocratic adventurer, Robert has no time or space for the elements of a still-rising capitalism: only a moneyed and educated “Friend” is capable of matching his freak.

Once Victor takes up the narrative, he tells of his pivot away from alchemy toward the natural sciences and chemistry experiments, culminating in the construction and animation of an assembled corpse — but this is handled quickly over a couple pages, without any fetid details sticking out.

What does stand out is a dream sequence, just before the revelation of Victor’s handiwork, with amazing graphic imagery of death and “grave-worms”:

I thought I saw Elizabeth, in the bloom of health, walking in the streets of Ingolstadt. Delighted and surprised, I embraced her, but as I imprinted the first kiss on her lips, they became livid with the hue of death; her features appeared to change, and I thought that I held the corpse of my dead mother in my arms; a shroud enveloped her form, and I saw the grave-worms crawling in the folds of the flannel. I started from my sleep with horror; a cold dew covered my forehead, my teeth chattered, and every limb became convulsed; when, by the dim and yellow light of the moon, as it forced its way through the window shutters, I beheld the wretch — the miserable monster whom I had created.

The action of these sentences, from the macabre vision to the view of the Monster, creates a parallel between the “sterile birth” of a golem with the closed circle of quasi-incestuous love; and undergirding all this perversity is the un-procreative nature of gay intercourse.

There may very well be a hard truth to confront: the brilliant Mary Shelley was a fugoshi.

The most sympathetic character of course is the Monster, whose arc anticipates an existential journey of suffering in a cruel universe. It’s not that he was thrown into it by Victor’s experiments, but that Victor chickened out and ran away, from both the Monster’s “ugliness” and his own responsibility. As the Monster says to Victor: “Unfeeling, heartless creator! You had endowed me with perceptions and passions and then cast me abroad an object for the scorn and horror of mankind.”

That’s a spooky thought: what if God abandoned His creation out of kneejerk repulsion at the results?

The chapters relating the Monster’s testimony are fascinating: the details of favoring the moonlight, witnessing his reflection, discovering (promethean?) fire. This sequence of the Monster on the run has been a fertile ground for Marxian critics: there is a de-classing moment, where the Monster has fallen from the educated bourgeois world into the countryside, the domain of the uneducated peasantry, whose patriarchal households still make their own food and clothes. These parochial people can only react with terror:

The vegetables in the gardens, the milk and cheese that I saw placed at the windows of some of the cottages, allured my appetite. One of the best of these I entered, but I had hardly placed my foot within the door before the children shrieked, and one of the women fainted. The whole village was roused; some fled, some attacked me, until, grievously bruised by stones and many other kinds of missile weapons, I escaped to the open country and fearfully took refuge in a low hovel, quite bare, and making a wretched appearance after the palaces I had beheld in the village.

As for Victor, he also reflects on the peasantry in terms of his obsessive revenge quest on the Monster, specifically in terms of the primitive accumulation process, of the peasantry’s dispossession and proletarianization:

If he were vanquished, I should be a free man. Alas! What freedom? Such as the peasant enjoys when his family have been massacred before his eyes, his cottage burnt, his lands laid waste, and he is turned adrift, homeless, penniless, and alone, but free.

And even in this reflection, we note, Victor regards the Monster essentially as something he owns.

This 1888 edition includes an introduction by Shelley, and she recounts that legendary holiday in Geneva when she and her friends were first inspired to write stories that were up to snuff with the Germanic folk tales they were reading and translating, and it includes more details than what I had gleaned from the material from Lord Byron and company. Why’d she do Dr. Mark Polidori like this?

Poor Polidori had some terrible idea about a skull-headed lady, who was so punished for peeping through a keyhole — what to see I forget — something very shocking and wrong of course; but when she was reduced to a worse condition than the renowned Tom of Coventry, he did not know what to do with her, and was obliged to despatch her to the tomb of the Capulets, the only place for which she was fitted.