Susan Howe. Concordance. New Directions, 2020. 108 pp.

It’s time to break up the monotony of novels with a letter on your host’s favorite American poet, Susan Howe.

Howe might be thought of as everything to everybody, to the extent that an American poet can be: an avant-gardist from the Language poetry circle, a regionalist of New England, a radical poet of feminist polemic. But more fundamentally, reading Howe’s poetry is like burrowing through a personally-curated museum of Anglo/Irish/American literary history, especially of the 18th and 19th centuries, from Swift to Melville to Henry and William James, essentially — and with Emily Dickinson in the center.

Layers of text, romance, nursery rhyme, and mythology are coordinated by a literary intelligence that may be speaking from a primordial past, or outside of time. Howe may very well be a practicing transcendentalist, in the path of Emerson and Thoreau.

Howe has been fascinating to read ever since I picked up Quarry ten years ago, which links Homer to Charles Sanders Peirce. The reading experience is maybe like Howe’s way of communing with archival texts. There’s a new collection publishing later this year, and I wanted to prepare with Concordance from 2020.

The collection’s opener, called “Since,” presents a kind of writing Howe took up recently (in the 70s and 80s she was known for strictly 1-page poems), but it’s what drew your host in to her work.

This is an extended prose poem, but also an autobiographical essay, except it’s not an integral narrative, but a collage of phrases and sentences from 19th century texts cut-and-pasted together.

These lines are enjoyable to read on a syllable-level: Howe is lowkey a “writerly,” sound-forward writer like James Joyce:

Here comes the scapegoat driven into the desert undo her necklace. In the Ark of the Constitution what we know and should have known

Short dream about being treated being treated badly by a professor in memory of friends and colleagues who knows why I cannot find or win. Doves as gulls carrying marriage messages breaking through initial particulars maybe this is world life saving’s time from an art-historical perspective at the cusp of post-WWII and postwar Cold War Brutalism.

The pages spell out a “trivial” historical connection. The great poet Emily Dickinson was once gifted a concordance to Shakespeare by judge Otis Lord, on the Massachusetts supreme court. When the judge got sick, his seat was filled by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr: presented here with a newspaper clipping from the New York Times, December 1882.

This Oliver Holmes insisted that his legal secretaries be unmarried men, reflected in a paragraph about “Swan Lawyers”: “My legal secretaries lost their way — a wrong turn of the pen — I don’t know why or how. Who are you Swan Lawyer Unmarried Male Maidens begging me to stay one day longer?” One of these “male maidens” was Mark deWolfe Howe — an ancestor of the poet??

From the accumulation of paragraphs we also vaguely get a sense of Howe’s literary upbringing as well as the mission of her poetry as she’s been composing it since the days of My Emily Dickinson.

Names stand out in a single isolation. Not for what they say or for what seems to remain unsaid stepping out as much as you like. Each slight verbal reference or connection gets lost though found by some inherent sense of form in every respect but touch linking the always undiscovered country to all families on earth. There is no other way Eve the unknowable author of life will live to teach others, bruising the Serpent’s head from years of treading water under history.

This is a dense network of associations. Why attach the adverb “always” to the famous clause from Hamlet’s famous soliloquy, I wondered. Perhaps it’s an allusion to the great Objectivist and Communist poet George Oppen. In any event, it’s not Adam naming creation in this story but Eve “the unknowable author of life.” To be “treading water under history” sounds like the reading experience of Howe’s poetry, which actively plums the obscurest parts of literary history. In the mainstream story, Eve was a Pandora-like woman, a gift and a curse. In Howe’s counternarrative, Eve is the true teacher who has been silenced, marginalized, given a bad rap by the authoritative texts.

The paragraph continues:

Ideas are her undercover only shells remain as placeholder keeping her spiral self safe somewhere far off she lays siege to your heart in spirit of the occult as the setting-into-the-work-as-truth made to blend others so that wrath is not the last thing, knowing birth is identical with death, and even mercy seasonable in days of affliction. This has something to do with ecology with what lies buried on the ocean floor; shields and sails and ships cast down, eons before house and home even before time as the roofed gateway in which a bier is placed before again disappearing.

These lines extend the “plundered” associations, deep under a body of water, “buried on the ocean floor.” But Eve or the literary force is salvaging (plus salvation) the nearly-lost shells and sand dollars.

Howe will also compress what Frye called “the rhythm of association” into a single line:

Lyric, Lyrica, lyre, liar, lawyer

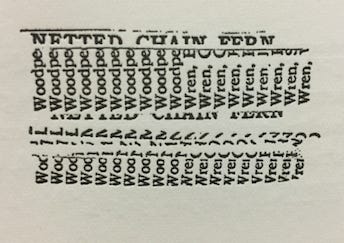

The centerpiece of this collection, “Concordance,” exhibits another mode of Howe’s, sitting on the frontier of poetry and visual collage or painting. These are facsimiles or microfilms of archival texts, cut up and rearranged into minimal compositions.

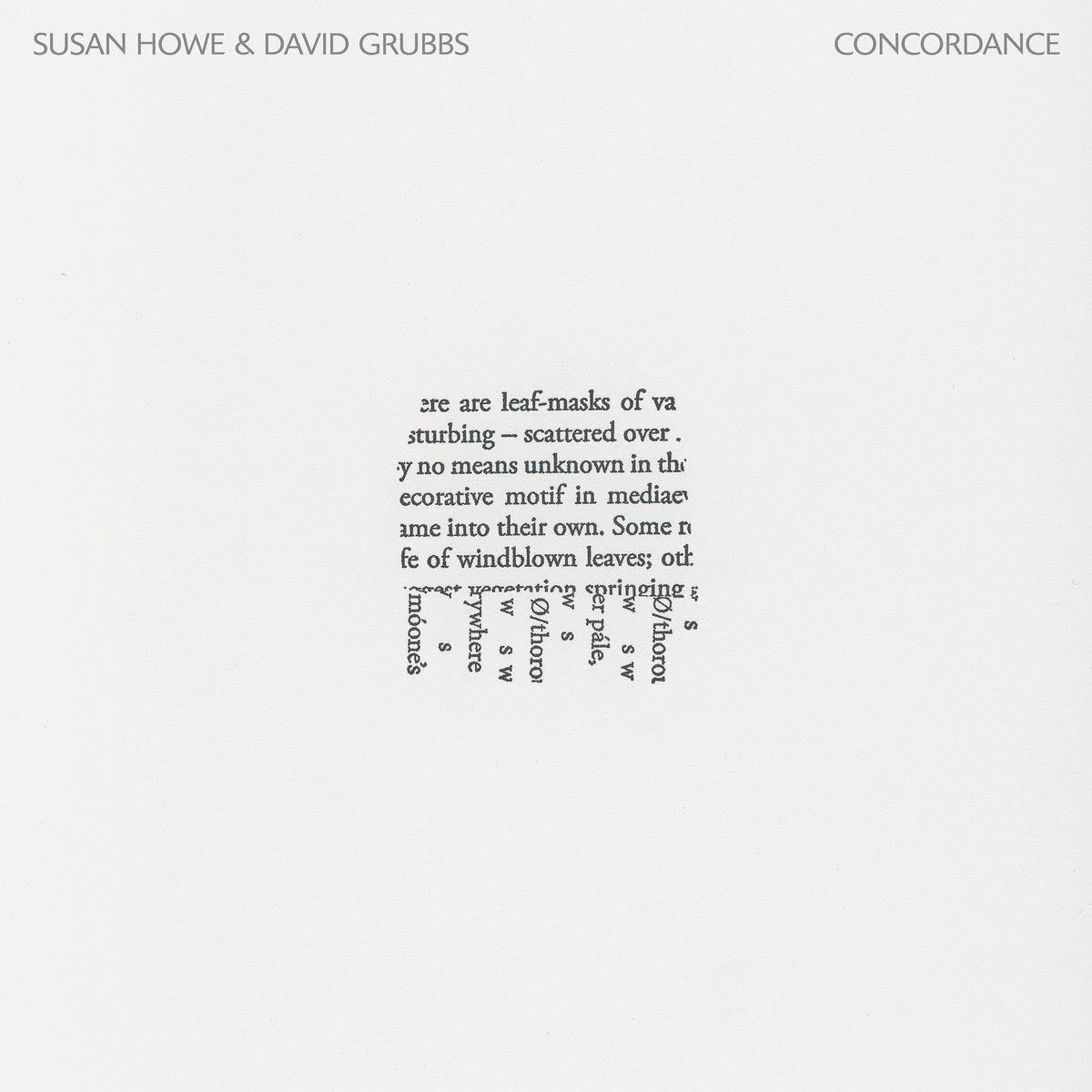

Howe recorded a reading of this sequence with minimal piano music by David Grubbs, and your host was gratified to see one of the most striking collages used for the album cover.

A cut-out from what may be an art history text, about some ornamental element in some product of the middle ages (manuscript lettering? drop cap designs?) sits atop a perpendicular piece from I’m guessing an obscure linguistic reference book, whose lines dangle out like the the tentacles of a jellyfish. (And “thorou” “thorou” is tauntingly similar to Thoreau.)

The “leaf mask” mentioned the upper text called to mind the Green Man, but in any case leaf might be semantically transformed into the leaves of a book while it gets “scattered” and “windblown.”

These square cutouts can still be remarkably coherent, like the second piece:

Concordances, I may remark, are

hunting down half-remembered

worthy service. They contribute n

e history of words, and so to the

ined such assistance from them

The concordance, as an index of words, is a means of “hunting down half-remembered” phrases, for instance from the Bible, or Shakespeare’s dramas. A “worthy service” indeed. As a form of organization, they “contribute [to the] history of words” in a way perhaps similar to etymology, or because a concordance will reflect what words were considered principal at the time of its making.

Some of the text-pictures are slashed to ribbons, literally. In one of them, you see the heading “HABITATS: WATER” (that must be from a book about birds) above a table of X’s and O’s, a tiny sideways line spelling “[S]hri” perhaps as in “shrike bird,” and beneath that another heading in a different style: “ROTATING PRISMS.” And those capitalized words are an emblem for Howe’s poetics: all we have in the present moment are the transmissions from history, presenting only one aspect at a time — but there’s something solemnly lovely or sacramental about this situation.

According to the book’s back copy, the primary sources for “Concordance” include Milton, Swift, Herbert, Browning, Dickinson, Coleridge, Yeats, “various field guides to birds, rocks, and trees.” (One column of repeated words whimsically phase-shifts from “sparrow sparrow sparrow” to “swallow swallow swallow”.)

Much of the fun of these collages is the visual, even painterly interest of setting different kinds of typefaces against each other, thin and dense ink, serif and sans serif fonts, English, Japanese, and ancient Greek orthographies, etc.

The bookend piece, called “Space Permitting,” is interesting in that the raw ingredients for its composition may be available online. They come from handwritten notes Thoreau sent to Emerson, regarding the search for Margaret Fuller’s body (plus the MS of the history book she was writing) from a wreck near Fire Island, which are archived here.

In this mode, Howe has the “squares” of text typed out, double-spaced, and centered on the page, the kind of layout you might see on the dedication pages in older books. They seem to be collaged granularly, at the clause-level.

Who were there first when

we got to the house to help

the latter lift up a child in

his arms but when they re-

turned for her the sea had

washed her away he saw a

silk dress lilac ground mid-

There’s a tantalizing ambiguity from the formatting: did “they” really “return” in the original context of that phrase?

Like Emily Dickinson in the nineteenth century and Gertrude Stein in the twentieth, Susan Howe is an “utterly astringent formalist” in the words of the great critic Peter Quartermain. She plays a delicate game, but it’s serious too, almost ritualistic, a game of “collage” that pits not just the “worlds” of texts and their constituent words, but also, to take a step back, the sense of coherencies of these worlds of story and language.

Next week: Laszlo K. takes us to war!