W. G. Sebald. Vertigo. Translated from the German by Michael Hulse. New Directions: 2000 [1990]. 263 pp.

Sebald, one of the most influential authors from the last decades of the twentieth century, was born in a German town known in his books as “W.” (W for Wertach.) He spent much of his life teaching in England, and while he wrote his novels in German, they have a cosmopolitan sensibility. His career was cut short when he died in a car crash in 2001, age 57.

With just four short novels — Vertigo, Emigrants, Rings of Saturn, Austerlitz — Sebald legitimated a type of fiction that works like a sheaf of memories and trivial scraps from history, held together by loose circumstance and expressed through the deadpan narration of a man walking around, sitting in cafes and trains, looking at artworks, getting his passport renewed (there’s a picture included in the book). These are definitely fictive novels, but they feel credible enough as travelogues or an old-fashioned type of newspaper chronicle. The soft-spoken narrator often gives up the “I” pronoun to include stories of other people, locals he talks to, or historic figures.

Vertigo, the subject for this letter, was his first book and it truly reads as a genesis for his whole procedure. Sebald didn’t make it into the international spotlight, however, till The Emigrants, which applied his method and concern with memory to the Nazi genocide. Your host read Rings of Saturn many years ago, having only just started to write seriously, but I didn’t really come back to Sebald till now, and I hadn’t even expected to do so.

I’m iffy about Sebald for two reasons, and they aren’t really even his fault. (1) Like Dostoevsky or Soviet-era novelists, Sebald’s work gets utilized for mainstream liberal historiography, as some moral bulwark against “totalitarianism” and all that claptrap. (2) Sebald was maybe too influential. There’s a whole brood of contemporary novelists searching for the “Sebaldian,” but they only make loosely structured ramblings with awkward interpolations and superficial exposition.

One of Sebald’s children is the Spanish writer Agustín Fernández Mallo. I had been reading his The Things We’ve Seen (2018) to catch up on my translated literature pile, but his use of photographs, urbanism, and anecdotes about history and art reminded me of Sebald, so I started reading Vertigo on a whim, and ended up finishing the Sebald and abandoning the Mallo. I might be unfair, but it felt like Mallo was repeating Sebald without innovating on him — unless adding pop culture references and global warming is an innovation.

But back in 1990, before Sebald became a world-class author, he began his experiment in modeling historical consciousness with Vertigo. It all starts with a story about a French soldier in the Napoleonic wars named Marie Henri Beyle.

Beyle marches across the alpine mountains into Italy, and the things he saw hit the young man’s constitution hard:

“…he was so affected by the large number of dead horses lying by the wayside, and the other detritus of war the army left in its wake as it moved in a long-drawn-out file up the mountains, that he now has no clear idea whatsoever of the things he found so horrifying then. It seemed to him that his impressions had been erased by the very violence of their impact.”

Beyle sketches a diagram: a view of the mountainside where he was marching and the fortified village of Bard. The author’s location, marked with an “H” for Henri, is at the hilltop on the left side. “Yet, of course, when Beyle was in actual fact standing at that spot, he will not have been viewing the scene in this precise way, for in reality, as we know, everything is always quite different.”

Why didn’t Beyle draw a first-person view or something like that, while representing his memory, especially of such an acute moment? Because other aspects of that place made an impression on him: “…the beauty of the descent from the hieghts of the pass, and of the St Bernard valley unfolding before him in the morning sun…”

And the choice of a high-angle view?

It was a severe disappointment, Beyle writes, when some years ago, looking through old papers, he came across an engraving entitled Prospetto d’Ivrea and was obliged to concede that his recollected picture of the town in the evening sun was nothing but a copy of that very engraving.

This is why engravings, photos, postcards, Instagram posts — any and all mechanical-visual reproductions are evil: they’re displacing our real memories of experience!

Now is the time to clarify that Marie Henri Beyle was not just a random French soldier bivouacking in Italy, but was the real name of one of the great writers of the 19th century, Stendhal. You don’t really need to know this (or that a character later on known as Dr. K. is in fact Franz Kafka) to appreciate the ideas put forward here.

Aiding our memory involves plotting: I mean drawing charts, maps, and diagrams, like Beyle’s sketch of the valley, with letters standing in for people and things. A plot is made of lines, which express the relations between variables.

Beyle’s/Stendhal’s line drawings, doodles, and scratching of initials, which I assume Sebald found in Stendhal’s autobiography, are visually intriguing. You can see his line degenerating in the late 1830s-early 40s, as he succumbs to syphilis.

There are other pictorial elements too, namely a ravishing image of Angela Pietragrua, whom Stendhal crushed on for 11 years and only then courted. You’ll see the picture in this post on a Sebald-centered blog, and how it was modified for the final version of this fiction: Sebald overlaid a 4x4 grid on Angela’s portrait. The blogger shrewdly suggests that “something about this image is unfinished or — more properly — ready to be taken to the next stage.” It’s like Angela’s picture is still in process, as if someone were about to enlarge it by hand using the grid method.

That work is analogous to remembering, too. The memory is a different representation, it’s the drawing based on a reference, or the plot. Sure, in one sense it’s a distortion of the “original” in the process of transferring it. But in another sense it is a rationalization, a concentration of tons of elements into something simpler but presenting the essentials. The grid disrupts and obscures with its straight lines, but it also introduces a rigorous order to our knowledge.

Besides, you might feel about memory and experience the same way as the main “Sebaldian” narrator does. A bit later in Vertigo, he is also taking a trip to Italy, but he’s both disappointed and discomfited by experiencing real places, and prefers the representations:

I sometimes think I would have done far better to stay at home with my maps and timetables.

It is not a coincidence that Sebald’s fictive project begins with Stendhal in Italy. Stendhal’s influence on the English-German novelist is immense: they both wrote stories that read as near-credible reports, combining primary-source fact with fiction. And they were both Italophiles, apparently.

But while Stendhal’s blend of forms was for pastiche and credence, Sebald’s modernist writing adds an eerie element of vertiginous totality of elements, so that a trip, a tiny region, a conversation, a piece of history — are all exchangeable and evenly suspended in a memorial hyperspace. Such is the method of Sebald’s narrator:

I sat at a table near the open terrace door, my papers and notes spread out around me, drawing connections between events that lay far apart but which seemed to me to be of the same order.

A brief passage within a long paragraph is fascinating for the transition, specifically how Sebald doesn’t land it. The bus transit out of Limone that must have happened is evoked in the negative:

I went into a bar near the bus stop, ordered an espresso, and soon became so deeply absorbed in recasting my notes that I have not the faintest recollection either of the hours of waiting or of the bus journey to Desenzano. Not until I am on the train to Milan do I become visible again to my mind’s eye.

These lines express a rich thought that I like to think helps generate the “Sebaldian” text. Namely, a thought of memory as the self being visible to itself, or to its imagination (“mind’s eye”).

As the novel winds down the narrator moseys through his hometown W., and recalls looking at old atlas books from the previous century in his childhood.

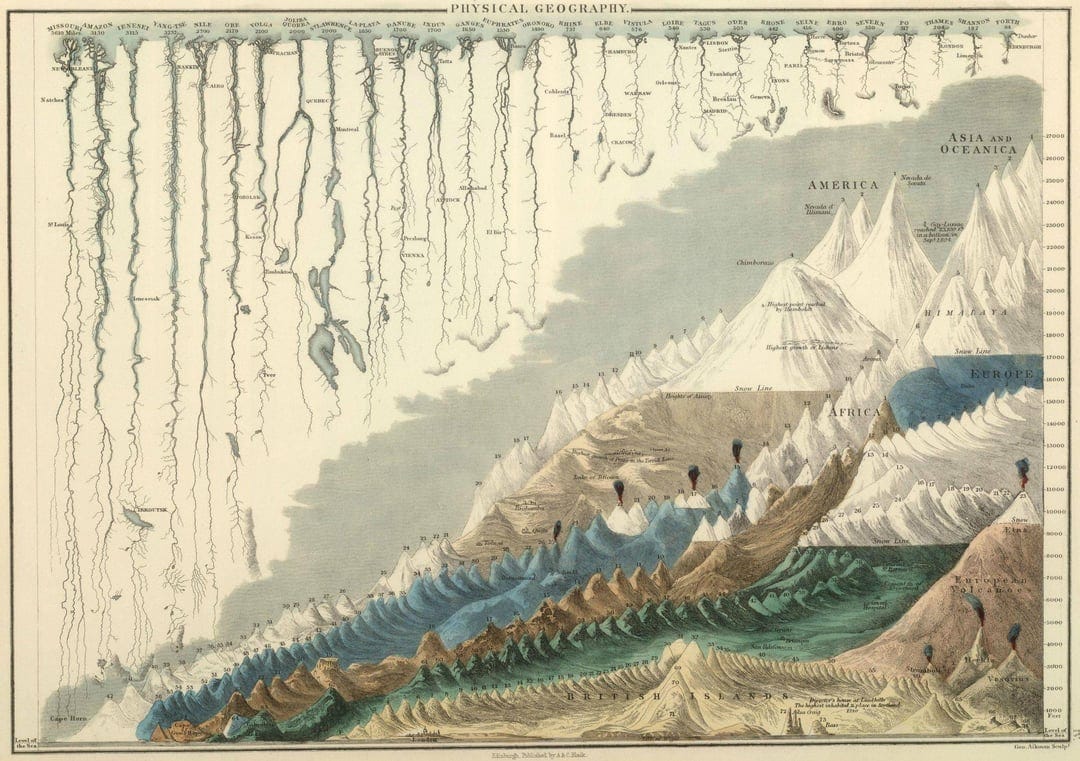

In the atlas there was a page on which the longest rivers and the highest elevations on the surface of the Earth were arranged by length or height, and there were wonderfully coloured maps, even of the most distant, scarcely discovered continents, with legends in tiny lettering which, perhaps because I could decipher them only in part just like the early cartographers were able to picture only parts of the world, appeared to me to hold in them all conceivable mysteries.

(To give some perspective, this cool “map” comes from the mid-nineteenth century, around the same time Melville published Moby-Dick, in which Ishmael mentions that the source of the Niger has not been discovered yet. Indeed the African continent had still not been fully mapped.)

One more thing: reading Vertigo forced me to revise my opinion of Sebald being a humorless writer. One of the books biggest yuks comes near the end, where the narrator inserts a ridiculous caricature, but in a syntactically interesting way: an extended interruptive clause inside a long sentence of travel reporting:

The following day, after changing several times and spending lengthy periods waiting on the platforms of the draughty provincial stations — I cannot remember anything about this journey other than the grotesque figure of a middleaged chap of gigantic proportions who was wearing a hideous, modishly styled Trachten suit and a broad tie with multi-coloured bird feathers sewn onto it, which were ruffled by the wind — on that day, with W. already far behind me, I sat in the Hook of Holland express travelling through the German countryside, which has always been alien to me, straightened out and tidied up as it is to the last square inch and corner.

That “gigantic” “middleaged chap” reads like Sebald’s take on Dickensian fiction, a line of “British” narration appearing in the context of “German” travels. But his “hideous, modishly styled Trachten suit” also I think points toward some kind of Austrian or Viennese-style philistinism that he wants to distance himself from, hence the strong reaction.

Recalling that Sebald (like Conrad) relocated to England (though unlike Conrad did not create literature in English), the narrator is also distancing himself from the place he’s in, for Germany’s landscape resembles the plots and graphs, “straightened out and tidied up” that have populated this narrative.

And it strikes me now that this whole long sentence is structurally a haiku of the book: a journey; a set of curious things, seemingly out of nowhere; and it tapers off into personal thoughts. Whatever it was Sebald was doing with these novels, it’s not as easy as it looks.