Rodrigo Fresán. Melvill, translated by Will Vanderhyden. Open Letter, 2024 [2022]. 308 pp.

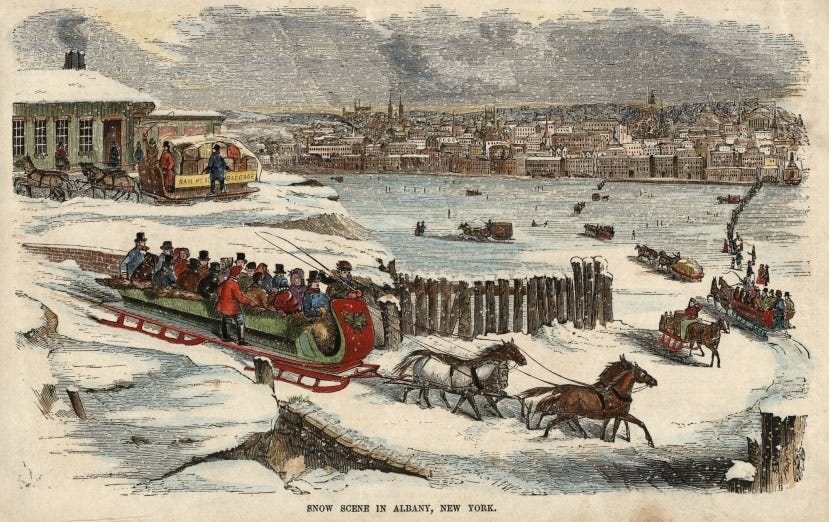

Two hundred years ago in Albany, New York, you could witness the famous “Albany Sleighs,” long enough for eighteen riders sitting two abreast, made of the finest wood and steel, painted in Christmas colors, and pulled by four horses past the snow-capped wooden fence posts, down to the frozen Hudson River. During the winter, until the early twentieth century, the Hudson had regularly turned into a blinding white highway, convenient for folks travelling by horse or foot.

The river ice left a big impression on Herman Melville — or Melvill, as he was before 1832. Early on in his capacious and symbolic novel Moby-Dick, the White Whale in Ishmael’s mind’s eye multiplies into a parade of floating icebergs:

the great flood-gates of the wonder-world swung open, and in the wild conceits that swayed me to my purpose, two and two there floated into my inmost soul, endless processions of the whale, and, mid most of them all, one grand hooded phantom, like a snow hill in the air.

The “processions” of whales, going two by two, are also like the breakup of the ice floes in the Hudson.

And again, when Ishmael studies the painting in the Spouter Inn, he speculates its forms might be, among other things, “the breaking-up of the icebound stream of Time.”

The “icebound stream of Time” is what Rodrigo Fresán centrally takes up for his latest book Melvill, which was translated fast as lightning by Will Vanderhyden. The publishers must have known this exercise in the “novel about a talented novelist” genre would be a hit — y’know, relatively speaking. It did pick up the Republic of Consciousness prize last year [and in the past week won Big Other’s book prize — Ed.].

It is Herman’s father Allan who walks the icebound Hudson in the dark of night. The river of ice is the universe and the duration of a life.

Just as my father took in a whole universe crossing a river of ice, I now contain my own meager existence, as I sail the streets and avenues and canyons and ravines of the cosmic Manhattan. The place where I was born. …

I’ve been fascinated with the Argentinian author Rodrigo Fresán ever since I picked up The Invented Part and got roped into this vast and energetic fictive world, a world experienced like a giant seething mass of pop culture and pulp science fiction, very similar to YouTube Poop (complimentary).

Your host intends to revisit Invented Part and the rest of the trilogy of which it is part, including Dreamed Part (which I found less thrilling) and Remembered Part (which I couldn’t even progress past the opening pages) — but there’s something compelling about Fresán’s worlds of 70s pop-culture cruft, delivered in such a contemplative style.

Despite the romance of whizzing spaceships and quantum ghosts and mythological creatures, Fresán’s books bend overwhelmingly toward interiority of the Proustian type, with entire landscapes and buildings made half of memories and half of dreams. Often a protagonist does nothing but sit in a room, Malone-style, and look at a representation in front of him, like a TV.

Or, in the case of Melvill, a failed businessman (his wife Maria Gansevoort added an ‘e’ on the end of the family name, as if to obscure this ignominy with a bid for ‘French’ dignity, or avoid creditors) is on his deathbed facing “the increasingly antiquated landscape of his own two portraits.” This fiction imagines that a young Herman watched his dying and feverish father, tied up to prevent his raving, and the indelible trauma sent him on his own artistic journey.

Divided in three parts (Fresán is fond of the three-book ‘fix-up’ structure of pulp science fiction, as well as Victorian triple-deckers), the novel traces a path from a strait-laced third-person history to the subjective monologue of Melvill Senior, and then finally, a voice that had only existed in footnotes in that first, most “non-fiction” part — Herman’s voice — literally sizes up and becomes the main body of the text.

And so the son replaces or becomes the father, at the typographical level: “the same dimension and magnitude as the volume of brief main text at whose feet I was born…and ended up outliving.”

Beyond the three divisions, this novel has an episodic structure, much like Moby-Dick. Melville’s novel seems like a crazy autochthonous thing, part fiction and part reportage and part satire.

But as Herman mentions in a footnote “...one morning not long ago, in the bookshop of John Anderson, on Nassau St., I opened wide a copy of Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy. And among all those quotations of and references to others (on the blank page before that of the title and author, in the upper righthand corner…”. Indeed, Burton’s anatomy — a scholarly text that is itself sliced up — is the major precedent for Melville’s work.

Fresán is for sure also plugged into the anatomical semi-fiction channel: his books are stuffed with epigraphs and bibliographical essays, as if to pastiche 19th century history textbooks. And at the level of rhetoric, there’s still something Victorian about these compulsively balanced clauses, but the cadence is deliberately slow (appropriate for an “icy” fiction).

These lines are from Herman’s father in his ravings, considering that same Hudson river:

A river in repose.

A river posing.

A river like a museum piece titled Frozen River.

A river that is like the portrait of a river / mixed technique: water and cold. (315 mi / 507 km-14,000 sq mi / 36,000 km2.)

A river (the same river we crossed so many times in a boat, the river I once threw you into so you would learn to swim with that exceedingly paternal combination of love and malice) that, in a way, has forgotten that it’s a river in order to remember how to become something else.

A river that’s also a bridge over itself form which nobody will ever be able to throw themselves into that same river.

A river that — paradox — left without going anywhere but that will return with spring.

This middle chapter is of course the most free-flowing, as it is locked into Allan Melvill’s subjectivity, effectively his dying dream. In this dream he is walking across the ice on the Hudson, as he had once done to get home, and his son Herman is with him, step by step.

Someone has tied me to this bed and at times I’m furious and at other times I’m grateful for it: thus, immobilized, I’m free from doing anything, from not doing anything right. In this way, I can no longer do everything wrong, as usual. Bound and dying, I’m held in higher esteem than I’ve been in a long, long time. Elevated now by that eminence that at the outset can only raise a glass (to your health!) to the infirm and terminal imminence of the end.

Fresán’s rhetoric is filled with these semantic opposites that help lend that balanced character of these lines reminiscent of Victorian fiction. Of his wide field of influences, Maurice Blanchot may be an underrated one.

This dream includes Nico C., who is a fascinating, fictionalized counterpart to Allan Melville, and is also corresponds to Herman’s friend Nathaniel Hawthorne (Nat H.). Nico C. has an encyclopedic knowledge of everything past and future; he’s sort like a human library of babel. (And Allan Melvill has a system-building project of his own, the science of ice, or Glaciology — “I realize now that my Glaciology is, in truth, in reality, Melvillology.”)

Nico C. speaks of innumerable things, including Mary Shelley and her creation of Frankenstein:

And her novel is, will be, constructed out of pieces. And I love this insistence among fictions of the fantastic on being composed of letters, newspapers articles, journal entries… As if in that way the authors thought that would make them seem more plausible and realistic, when actually, without realizing it all they’re doing is denouncing the easily torn fabric of our misnamed reality and of the supposedly real…

There is an interminable discussion on this point amongst bookworms, but for this novel, Mary Shelley’s great story stands in for the birth/invention of Science Fiction, which is not really a negation of Fantasy but the placing of Fantasy on a higher, “technological foundation.” It’s “a good sign that the times are changing for the better,” says Nico C.

As Herman’s voice takes the floor, we learn about this character’s own reflections about what it means to make serious fiction, through his relationships with others, his family, his father of course, his buddy Hawthorne, and the great poet Walt Whitman:

And warning: once there, nothing interested me less than containing multitudes (though my style has always been marked by a certain referential mania and citation compulsion that leans on the pillars uniting and sustaining the King James Bible and the fury and madness of the royal Macbeth and Lear and by a burning frenzy of metaphors and by the deep conviction that there are certain enterprises for which a careful and well-planned chaos is the best and truest way to achieve them). What I did aim for was to be contained by multitudes.

Or a parenthetical will articulate a thought of the social function of a “Great American Novel”

(though I am sure that no nation can consider itself true and worthy of respect and fear of all others until it has produced fictions of its own that help it believe in itself and other nations of the world to believe in it, and that I wanted and believed myself to be part of that process so that I could believe in myself)

It’s easy to lose one’s bearings in the sliced up floes of prose, and get lost in the forest of ideas:

I detest thinking about the titles and themes of my work as if they were accidents written in a ship’s log or symptoms exhibited before a medical tribunal to defend myself from those tormented and tormenting reviews, like straitjackets or supposedly therapeutic immersions in freezing water or iron cages in which to imprison a mind that thinks too many mindless things.

I hate thinking about thinking about myself like this.

But the narrative winds down smoothly, and then we’re treated to the back matter. Fresán ends his novels with a final section that is like a corpus of cultural texts and further thoughts from the author himself, including quoted passages from other books, like this missive from The Remembered Part, that wryly comments on the whole Novel-about-a-novelist phenomenon:

They weren’t interested in literature but in being able to say they were interested in literature and — like proof, like someone repeating an alibi — having a couple anecdotes to regale people with at parties…

Considering these passages and more, Melvill commands an “auteurist” reading at the ideational level of the author himself. That is, the book is explicitly a victory lap for Fresán after the completion of his Three Parts. But I can’t deny it’s an interesting one.

![Melvill [Book] Melvill [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!9ILA!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F03d68d01-92f5-47bb-9a6e-d6a3f570e0b6_1650x2550.jpeg)